To search the RPR site click here

A discussion; and a comparison of some drawings with more recent photographs

As we have shown elsewhere, Pitt-Rivers' believed that art could represent 'Truth'; that it was possible for an artist to accurately represent a three dimensional object in a 2-d drawing. This belief is reflected in his employment of skilled draughtsmen to compile the catalogue of his second collection after 1880.

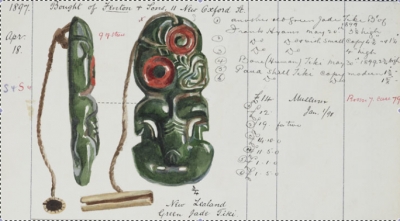

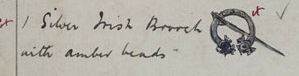

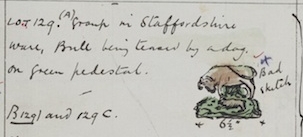

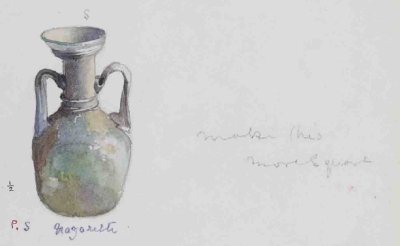

Obviously the exact working methods of the assistants are not known and it is clear that great attempts were made to render the objects accurately, for example from the middle volumes an attempt to measure the scale is made with items being annotated '1/2' (one half actual size, presumably) etc. As the artists were also producing site plans etc to scale for the archaeological excavations, one would presume that they brought some of that methodology (and technology) to the task. Sometimes comments were made in these catalogue entries about the standards of the drawing or how much they resembled the artefact itself. These were presumably made by later museum staff who were endeavouring to find the artefacts depicted in the catalogues or trying to match found artefacts against the illustrations. Some examples of these comments are provided here.

It is clear that accuracy was important to Pitt-Rivers. Bowden tells that W.S. Tomkin (one of his original assistants) had to 're-draw both skulls and coins for the first Cranborne Chase volume because the General was not satisfied with the accuracy of his first drafts. [Bowden, 1991: 104]

One intriguing thing therefore is that, late in the series around 1899, it is clear that Pitt-Rivers did inspect the volumes. See his signature next to an illustration in the book to witness his approval, presumably of the accuracy of the drawings. There are only three incidences of this being noted, the handwriting is shaky in all instances, it may be that by this date the books had to be taken to Pitt-Rivers to be inspected as he was ill. All the notes are dated the same, February 5 1900, a matter of weeks before his death. The second is on page 2158 of volume 8 and the third page 2301 of volume 9. [Note: for pedants, Pitt Rivers does not hyphenate his name in these instances]

Many of the drawings, after the first book, appear to be very accurate indeed in so far as they present a very 'life-like' appearance. Some were clearly never meant to be more than sketches, for example the sketch of the buckle described in this article. However, to truly judge this one would need to place the actual object and the illustration side by side.

An obvious questions is 'Why did Pitt-Rivers not use photographs to record his acquisitions rather than watercolours?' The solution is obviously unclear and possibly unknowable, but a partial answer is that of course he DID use photographs, but not very often. We coudl surmise that he favoured the illustrations as showing a greater truth or accuracy. Some of the illustrations are in fact black and white photographs which have been coloured, though there are not many of these. It is clear, therefore, that he had access to the ability to photograph images.

Corroboration of this is given by a series of letters given here, and here. In the latter case an author asks for access to one of the objects (a model of a boat in terracotta) in order to illustrate a publication. Pitt-Rivers is reluctant to loan the object and suggests that an illustration be made in London by the author's artist from a photograph. He did not suggest that an illustration be made by his draughtsman. I think this must be down to time, it was far quicker to photograph even then than it would have been to draw and colour. Pitt-Rivers felt sufficiently kindly towards the project to invest a little of his staff's time but not a lot. It surely cannot be because the photograph was felt to be more accurate. Sadly the book appears never to have been published so these photographs and the resulting pen-and-ink drawings and resultant plate are probably lost (if they were ever completed).

The obvious answer is to compare the actual objects to the drawings, or as a second option, compare more recent photographs with them. This is, of course, not possible for the majority of the objects as the collection is no longer publicly available or all in one place. However, opportunities did present when objects from the second collection were later acquired by the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford as occurred in a small number of cases. See below for some examples. Other opportunities are afforded from the sales of items from the second collection from the 1950s onwards. Where the sale catalogues from the auction houses include photographs, it has been possible to match the objects to the drawings.

Finally, how accurate are the drawings? You can make your own mind up.

See here for more detailed comments about the images.

The first three images are of Add.9455vol4_p1512 /1 from the catalogue, and from a recent sale in June 2010 when the tiki was purchased by an unknown purchaser for over 23,000 euros, see here.

These images show a downside of the catalogue illustrations; they seldom show the back of the object. This is a good opportunity to see that they were identified by text written on them, presumably by Pitt-Rivers' assistants, though it might have been by a subsequent owner.

The following images compare one of the earlier, smaller drawings (which obviously contain much less detail) with a photograph of the object by the Metropolitan Museum at New York who currently own it

The following illustrations are made by G.F. Waldo Johnson and are much more detailed, in fact the first drawing actually occupies an entire page, so good is it that it has hardly any additional textual information associated with it:

Note that the foot of the Benin horn-player was added by the Metropolitan Museum, New York in the early 1980s. See ‘Bringing African Art to the Metropolitan Museum’ Susan Vogel African Arts, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Feb., 1982), pp. 38-45, page 38.

In some instances remarks are made in the catalogue itself about the images, in the following case the remark is derogatory, suggesting that the drawing is not thought up-to-standard though a comparison to a later photograph of the same object suggests it is not too bad:

More comparisons of drawings and later photographs here and here.

Further Reading

Bowden, Mark 1991. Pitt Rivers: The Life and Archaeological Work of Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, Michael and Colin Renfrew. 1999. ‘The catalogues of the Pitt-Rivers Museum, Farnham, Dorset’ Antiquity vol. 73 (no. 280) pp. 377-392

AP, April 2010, updated and substantially changed February 2011

![Seen and approved? [Add.9455vol7_p2093 /2]](../../component/joomgallery/seen_approved_20100322_1695949185-view=image&format=raw&type=img&id=281&Itemid=41.jpg)