To search the RPR site click here

Drawing as record

Today all museum objects are routinely photographed when they are accessioned. These are digital photographs which are stored in a museum database to be used when an object is mentioned in a publication, in museum publicity or as part of the record of the object.

The Pitt Rivers Museum is no different. Unfortunately, at the present time the majority of these images are not available for members of the public to access easily. As a long term aim, the Museum wishes to routinely add these photographs to the collections management database entries for each object. They would also be made available to the public via the web interface with this database.

For the last ten to fifteen years, there has been a rolling programme of photographing the huge number of objects accessioned before digital photography was invented. Some of these may already have been photographed in non-digital format and have negatives stored by the museum. It is possible to digitalise this backlog although it would be a herculean task. At the time of writing the Museum is actively seeking funding to improve its photographic digitalisation and also the provision of images for its objects on its collection management system.

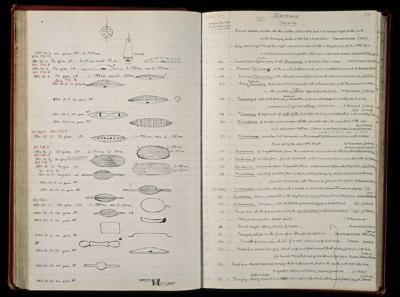

Before photography was routinely used for all objects, some objects were drawn in the accession books (see illustration on this page). Drawings were not done systematically, and were usually either only pen-and-ink or even pencil drawings (without coloration). In no way do these drawings compare in detail or sophistication with the drawings in the catalogue of Pitt-Rivers' second collection.

Drawing as 'learning'

The Pitt Rivers Museum has encouraged the drawing of objects as part of its teaching programme in the past. This follows on from the stance taken by Pitt-Rivers, who believed in what he called 'eye-training':

If it is true that no one can form true ideas in his own mind upon any subject until he has acquired the art of expressing them accurately in language, it is equally true that no one can take in an accurate impression of the things he sees in the world until he has acquired the power of drawing them correctly (Pitt Rivers 1884b: 8).

Pitt Rivers himself had always been fond of 'field sketching' as a soldier. [Bowden 1991:104] He taught the skill to his assistants and was a hard taskmaster, '[W.S.] Tomkin had to redraw both skulls and coins for the first Cranborne Chase volume because the General was not satisfied with the accuracy of his first drafts'. [Bowden 1991: 104]

After the founding collection was given to the University of Oxford, it was managed by university staff, in particular Henry Balfour, the first real Curator, who was in post for nearly fifty years. Balfour himself was a talented artist. It seems likely that the drawing of objects was an integral part of the care and recording of collections and the skill of accurately depicting objects was passed from the museum staff to the students who studied in the new museum. Many of these students went on to work in museums throughout the world and presumably exported their drawing skills.

Students being taught at the Museum were encouraged to draw objects as part of their study. In the 1947-8 annual report for the Museum, it was reported that:

Mr. Bradford also assisted Miss Blackwood in Practical work in Ethnology for Diploma students throughout the year, and the Curator in practical work in Archaeology and Technology. In both courses he successfully introduced drawing, which is much enjoyed, and shows good results in the Diploma Examination. Sir Francis Knowles continued to give instruction in drawing stone implements.

In 1949-50 the importance of close observation and drawing of objects was made even clearer:

During Hilary and Trinity Terms [Bradford] gave practical instruction, together with Miss Blackwood and Sir Francis Knowles, on archaeological and ethnological draughtsmanship, identification of material, interpretation of air photographs, social data from maps, and recognition of physical types ...

This continued at least until the 1970s. Today students do not study how to draw artefacts, nor how to knap stone tools in the Museum. However, students do study technology, particularly in a course run by Dan Hicks, Curator-Lecturer at the Museum, called 'Material Culture Studies'. This course is open to undergraduate and postgraduate anthropology and archaeology students. The wider cultural aspects of technology, trade, and consumption are considered.

To discover about the drawing game see here.

To discover more about teaching of technology and drawing in the Museum, see here.

AP, June 2010