To search the RPR site click here

The 1860s: The rise and rise of Lane Fox's collection

‘… once a beginning is established, it becomes easier to perceive the development of the plot of collecting … one can focus on either the objects or the collector as narrative agents, and again, their stories do not converge. The objects are radically deprived of any function they might possibly have outside of being collected items.’ [Bal, 1994:110]

The 1860s were arguably Lane Fox’s most productive period – the only other contender would be the 1870s. His collections appear to have grown during this period by leaps and bounds, he was very active in a number of learned societies, published a good deal and it was the first time that he carried out an archaeological excavation. He was of an age to be personally and professionally active as he was in his thirties and early forties during this decade. The only limits on his involvement in collecting and anthropological theorising were his professional commitments to the Army to which he was still actively committed.

Generalities

Professionally the enquiry into Lane Fox’s rifle training was completed and his professional life resumed. In 1861 he travelled to Canada on ‘special service’ as part of a deterrent force for some months, his only visit to North America. He spent part of the decade in Ireland serving near Cork as a quartermaster for the British Army stationed in Ireland (then part of the UK), from 1862-1866; this period marked his first archaeological endeavours in the field with his work on local raths. Although he was based in Ireland during this period he maintained a house in Chesham Street in London until 1865. After service in Ireland he returned to London in 1866. In the same year he moved to 10 Upper Phillimore Gardens, Kensington where he lived until 1873 when he moved to Surrey. In July 1867 (at the age of 40) he went on half-pay and was free of military duties for the next 6 years, still holding the rank of Colonel. [Thompson, 1977: 29-30] This gave him increased amounts of time to carry out work on his anthropological and archaeological interests.

Five more children were born to Lane Fox and his wife Alice during the 1860s. His fourth son, Lionel, was born in 1860, a year after his first daughter. Of all his children Lionel was perhaps the most interested in archaeology, taking part in excavations in Cyprus. Two years later in 1862 a second daughter was born: Alice (presumably named after her mother). In later life she married John Lubbock, one of her father's closest colleagues. A year later Agnes was born; she became a well-known author in later life and, unusually for a Pitt-Rivers child (it seems), she was educated in a school. Lane Fox's fifth son, Douglas, was born at the end of the next year in 1864. He became an unsuccessful farmer. Finally in 1866 Lane Fox's final offspring was born, another son named Arthur Algernon. He seems to have had some health problems and special provision had to be made for him in his father's will.

In 1861 he made his first moves out of Army-related hobbies of the 1850s into anthropology, joining the Ethnological Society of London in 1861. The following year he marked his increased involvement by the start of his larger scale purchases, when he probably obtained a large number of items from a sale at Bullocks on High Holborn – a collection of artefacts from southern Sudan collected by John Petherick. In 1865 he joined the Anthropological Society of London.

His interest in antiquarian and archaeology matters increased during this decade, he was nominated for fellowship of the Society of Antiquaries in London in 1863 and elected in mid-1864, and also joined the Royal Institution and Antiquarian Society in Cork in 1863. Finally he joined the Archaeological Institute in 1864 when he also first carried out an excavation in Ireland. His first paper to the Institute was given in 1866. He joined other learned societies in this decade, the Geological Society in 1867, the International Congress of Prehistoric Archaeology in the next year. From the mid-1860s Lane Fox engaged with wider public debate, joining the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1868.

By the end of the 1860s it seems that Lane Fox was into his stride so far as his collection was concerned and the shape of it is more familiar. Not only do we know about a reasonable number of purchases he made in this decade but also about other objects that clearly were obtained by him from secondary sources like other collectors etc. Objects from his collection began to be drawn to the attention of colleagues and the general public through an increasing number of public lectures and papers to learned societies, in 1868 he published Primitive Warfare, the first major publication of his career. By now the objects in his collection were not only obtained through dealers, auction houses and acquaintances but also from excavations and field-walking.

In 1869 Lane Fox had his first experience of organizating artefacts in a public display when he helped organize an exhibition at the Museum of Practical Geology.

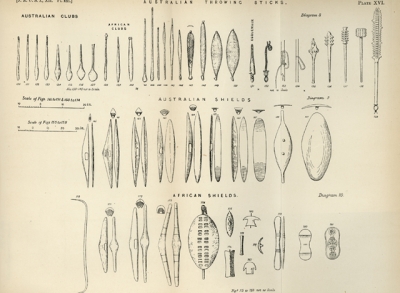

It is not clear how much work Lane Fox did on his artefacts before they went on display at Bethnal Green but it is clear from the illustrations used in publications like Primitive Warfare (1867) that he had already begun to arrange them into series. Indeed in some cases the series seem to have been more or less complete by then. For example the attached illustration of Plate XXI from Primitive Warfare II, presented to the United Services Institution in 1867, which shows Australian throwing sticks, shields and African shields seems to contain objects very similar to those shown on Screen 2 at Bethnal Green Museum in 1874 (according to the catalogue prepared for those displays). Which suggests that the series were being developed during the 1860s and possibly even as early as the late 1850s.

Specifics

More objects are clearly documented as having been obtained in the 1860s than the 1850s. These include a number of objects from the Royal United Service Institution who sold a large part of their collections in June 1861 via Sotheby’s. According to Chapman:

‘Included among Fox’s purchases [from RUSI] were a vase of undetermined origin, a model of a South American hut and a Swiss Cottage, a ‘Chinese wooden Harmonican’ and a small portrait of Boadicea. The prices in each case were low; the most expensive item was the Boadicea portrait for which he paid 10 shillings. [Chapman, 1981: 98]

Note that none of these items (with the exception of one, see below) appears to be in the founding collection. Chapman appears to have found out about them from two accounts of London by Bohn and G.W. Thornbury. The items that are recorded as coming from there, possibly in 1861 (though it might have been earlier) were an Indian helmet [1884.32.5] collected by Vincent Eyre, Japanese archery items collected by F.W. Beechey, Burmese bells and a stand, a West African marimba, and a Javan xylophone (which might be the Chinese harmicon mentioned above), a zither from Madagascar, and an axe from Norfolk collected by T.G. Bayfield.

There are more clearly signs of Lane Fox buying items for his collection. We know about 40:

1861 Items from Sothebys (from the Royal United Service Institution)

1862 Petherick collection from southern Sudan, probably purchased from Bullock, High Holborn, London

1864 Items purchased from John Windele

1865 Another collection from Petherick from southern Sudan

1867 1884.2.22-23 2 Padlocks Thames [February, unnamed source]

1884.17.11 and 12 Quiver and arrows from India Mishmi [probably bought from auction, source unknown]

1884.119.130 and 1884.140.923 2 Irish Axes [1 metal 1 stone] from B. Hastings

Item from Paris Exposition Universelle

1868 1884.119.348 Irish Bronze spearhead from Lord Guillamore

1869 1884.125.305 Stone axe from Bryce Wright

A total of approximately 1250 other items might have come in during the 1860s of which the vast majority could be classified as archaeological, many related to his excavations etc but some from other sources.

Of his archaeological objects acquired in the 1860s, many came from English archaeological sites. 264 were from London archaeological sites and therefore the product in his own archaeological endeavours (either of his own findings, or from others who were also researching areas of City of London (London Wall) and Thames gravels). A further 188 were from his expeditions to look at Sussex hillforts, 126 from Yorkshire, 121 from Ireland, 108 from Oxfordshire, 40 from the Isle of Thanet, Kent and 25 from his excavations in North Wales at ‘Carnedd Howel’ and small numbers from Stonehenge, Gloucestershire (Uley Bury), Grimes Graves, and Torbay which were probably found by him.

This is the breakdown of how many of his own found objects are date to each year during the 1860s

1860 0

1861 0

1862 0

1863 0

1864 66

1865 8

1866 177

1867 418

1868 220

1869 166

As can be clearly seen, Lane Fox’s archaeological activities increased significantly after 1864. Some items are only dateable to a range of dates (items obtained in Ireland which must have been obtained between 1862-6 and items from the London Wall and Sussex), these have been ignored in the above figures.

Aside from the above there were other archaeological items (some of which may have been purchased) acquired from other people:

1860 1884.122.476, 494, 497, 499. 501 Stone tools from Dr Hunt, from Amiens in the Somme region of France

1861 1884.37.10 Item of Samian ware from Wroxeter in Shropshire, unknown source

1884.132.3 Stone flake from Joseph Prestwich from Amiens in the Somme region of France

1862 Three stone tools noted as coming from Henry Christy from St Acheul in the Somme region of France: one being acquired in June 1862 [[1884.122.453], another in September of the same year [1884.122.486] and the third, 1884.122.461, acquired in New Year’s Eve 1862; Lane Fox also acquired another stone tool from St Acheul on New Year’s Eve 1862, which probably also come from Christy [1884.122.471].

1863 168 stone tools from Dordogne caves in France from Henry Christy and Edouard Lartet [1884.122.509 and on]

Stone tool from Trinidad from W. Hackett [1884.126.214]

1864 1884.127.56 Stone axe from Dunwich, Suffolk from an unknown source

1884.126.57 Maori stone tool from Robert Day

1884.122.102, 104, 105, 150, 160 Stone tools from James Brown collection from Southampton and Salisbury, another one from Salisbury was received in 1867 [1884.122.100]

1884.82.117 Brass armlet purchased from John Windele thought to be either Roman or African

1884.98.4-5 Ogham stones acquired from John Windele

1865 1884.133.72-73 Stone tools from Maiden Bower, near Dunstable, Bedfordshire from unknown source, (it is possible that they were from F.K. Porter, see 1867, or excavated by Lane Fox himself, further items were obtained in 1866 and (most in) 1870)

1884.125.132, 135-137, 141-4, 1884.132.42, 44 Stone tools from Danish middens and Salisbury Wiltshire (1884.122.153 ) from John Evans (note the second items are from the same site as the items from James Brown in 1864)

1884.120.68-70 Roman items from London from Bousfield acquired in May (more in 1866 and undated)1866 1884.125.58-63 stone tools from Maiden Bower, Bedfordshire from an unknown source (see 1865)

1884.122.70, 85 Stone tools from Shrub Hill, Norfolk (possibly a farm near Feltwell), from an unknown source. Lane Fox got more stone tools from the same place in June 1871 and undated. John Wickham Flower had items in his collection from the same place.

1884.120.74-75 Roman items from London, from Bousfield

1884.41.117-118, 162, 170, 1884.50.25, 1884.52.7-8 Roman ware and horse furniture from London from James Charles Clutterbuck dated June, October and November

1867 1884.11.62 Net float from Swiss Lake Dwelling from John Lubbock

1884.37.24, 107, 1884.41.161, 1884.85.11 Roman objects from London from James Charles Clutterbuck’s collection

1884.131.36 Stone tool from Pakistan from Colonel W.B. Dickinson

1884.30.52, Shield umbo from Saxon cemetery, West Stow heath, Bury St Edmunds, two other items from same site are dated 1852.

Stone tools from Denmark from unknown source [1884.127.63, 1884.134.8]

Stone tool from Frederick K. Porter from Bedford [1884.122.156]

1884.120.31-32 Iron tools from ‘JMN’ from Miller’s Dale Derbyshire acquired February 1867

1868 1884.41.67 Roman ware from London from James Charles Clutterbuck (see 1867 and undated as well)

Beads from Frankfurt Germany,

1869 1884.122.438, 450, 462, 474-5, 522, 1884.125.352, 1884.132.4-5, 99 Stone tools from the Somme region, Pas de Calais, Paris from unknown source

1884.126.127 Nicaraguan Stone tool from B.C. Seemann

1884.126.112-114 Stone tools from Florida from unknown sources

Stone tools from Lakenheath, Suffolk from unknown source

1884.41.119, 1884.104.78 Roman objects from London from James Charles Clutterbuck’s collection dated May

1884.119.108 Metal axe from Cambridgeshire from ‘I.K.P.’

1884.122.9-10 Stone tools from Brandon, Suffolk dated October from an unknown source

1884.122.21, 34, 109, 111 Stone tools from Santon Downham and Lakenheath, Suffolk dated July and September from an unknown source

1884.125.211 Stone tool from Guernsey from unknown source

He also obtained some ethnographic objects that are associated with definite acquisition dates:

1860 None listed

1861 Items acquired from RUSI via Sotheby on 24 July 1861, including items from Beechey

1862 None listed

1863 Heart in cist from Cork Christ Church, 1884.57.18

1864 1884.68.129 Shell pendant Solomon Ids, from an unknown source

1865 1884.30.63 A Peruvian shield from Edward Bartlett. Another undated item from the same donor and place was a bamboo shield [1884.64.1]

1884.82.129 Marble arm bracelet from Nigeria, obtained from H. Warren Edwards in August (there are other items from this source, but they are not dated except for another from 1866, see below), it came to Lane Fox before 26 January 1869

1866 1884.2.28 Padlock from Thames

1884.56.4 Amulet from Carnac, Brittany (possibly not obtained until 1879 when it was sent to South Kensington Museum)

1884.56.13-17 Arab arrow amulets from John Evans

1884.70.54, Brass ewer from West Africa from H. Warren Edwards

1884.56.13-17 Arrow amulets from John Evans

1884.101.13, 90 Pipes acquired from Joseph Dalton Hooker from Zulu, South Africa

1867 1884.2.23Padlock from Thames

1884.17.11-12 Quiver and arrows from Mishmi India purchased at auction

1884.19.36, 40, 42, 43 4 Solomon Islands spears from unknown source

1884.62.36 NZ storehouse door possibly acquired 1867 from Haultain or Hocken

1884.85.11 Tattooing feeding funnel Maori, New Zealand acquired by purchase from James Charles Clutterbuck

1884.11.63 Fishing club from Dr Dally 1867 from Vancouver Island

1884.112.19 Trumpet from Japan acquired at Paris Exposition Universelle

1868 1884.65.15, 1884.84.76, 1884.114.111 Head and masks collected by Dr Dally from NW Coast of N America, items from Dally are known to have been acquired by him in the field by 1870

1884.8.3, 1884.48.15, 1884.75.33 Firedrill, bag and neck ornament from Tasmania from Joseph Barnard Davis

1884.76.49-50 Beads from Namibia from ‘Gregory’

1869None listed

Note that when it is said that no items were acquired in that year, it means that no known items are dated to that year. It may well be that one or more of the undated items (which outnumber the dated ones) were obtained then but there is no evidence that they were to date.

According to Chapman, by 1869:

‘Fox’s collection had attained at least the basic outlines of his later museum. In all, it included materials from Africa, Australia, India, and North and South America, with further contributions from the Western Arctic and the South Pacific Islands. Donors had included Richard Burton [only small part of total collection], J.D. Wood [sic, most material from J.G. Wood came in 1870s] and Warren Edwards; major purchases had been made from the collections of John Petherick, Edward Belcher [sic, actually obtained 1872] and Richard Dunn. Archaeological material, some of it purchased, but most of it resulting from Fox’s own field efforts, had rounded out and, to a certain extent, supplemented exotic materials, bringing to the whole a unity of purpose. Included among the latter were pieces from France, Switzerland, Australia, Denmark, Ireland and England, as he revealed in his second lecture on primitive warfare. Again, most of these were original pieces; others were facsimiles or casts. The total number of objects is difficult to estimate but, the collection must have reached into the several thousands. [Chapman, 1981: 322-3]

This is more or less an accurate picture of the collection at the dawn of the 1870s. Some 30 years after Chapman wrote this we are no nearer having an accurate picture of the way Lane Fox acquired his collection or the exact timing of acquisition for the majority of his objects.

Exhibiting the collection

It would appear that the earliest object that Lane Fox exhibited at a society meeting is in 1861 to the Royal United Service Institution where he showed a model, however it seems clear from the text of the article that although the model is referred to as such, it is in fact an illustration rather than a physical model. This article was later published as, 'On a Model illustrating the parabolic theory of projection for ranges in vacuo', in 1861.

The actual first object displayed at a society meeting appears to be human heart in a lead casket (now part of the founding collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum 1884.57.18) from Cork Cathedral that he displayed to the Royal Archaeological Institute on 7 December 1866. It is known that he obtained this object in 1863 during his Army service in Ireland. [Chapman, 1981: 117] In fact, that month seems to have been a landmark one as a week later on 13 December he exhibited a peg-shaped object from Ireland to a meeting at the Society of Antiquaries. It is not clear what precipitated this new move to take part in learned society meetings, publically discuss the work he had been undertaking and exhibit objects but it was perhaps helped by the fact that in 1866 he left his posting as Quartermaster in Ireland and moved back to London where he seems to have had quite a lot leisure time to devote to attending learned society meetings and take an interest in the London Wall excavations that were taking place as part of the development of the City of London. In 1867 he took half-pay from the Army and effectively had much more leisure time

Again, in the ‘Primitive Warfare’ lectures he gave to the Royal United Services Institution between 1867 and 1868, the talks appear to have been illustrated by large illustrations or lecture aides (later turned into illustrations published with the paper). Many of the objects he refers to were not in fact, in any case, owned by him but were in the Museum of the Institution. According to Chapman on 28 June 1867:

‘To illustrate his talk, examples were presented both from his own collection and from that of the Institute. The latter were placed on display in the front of the lecture theatre for the benefit of the audience.’ [1981: 268]

It has also been suggested that Lane Fox used his own collections as examples in his charts showing the evolution of specific forms of weapons, illustrations used in the published form of his papers:

‘Fox’s second paper on primitive warfare provides perhaps the most complete picture of his ambitions up to that time, as well as the characteristics of his collection. The chart illustrating the transition from leaf-shaped to lozenge-shaped arrowheads corresponded to a series in his own collection, as did diagrams illustrating the relationship among simpler stone tools. The series on boomerangs, throwing sticks and parrying shields also grew out of one in his own house, and we can assume that his arrangement on paper at least approximated that on his walls.

Chapman does add though:

‘Other details, however, including the full extent of the collection remain largely a matter of conjecture. Those objects referred to during the course of it, as well as during the course of other lectures and discussions of around the same time, provide only an outline of the full contents of his collection at the time. Even then, it is difficult to tell which objects were his and which were merely illustrations or diagrams added to his collection in lieu of the actual objects.’ [Both quotes Chapman, 1981: 292]

As already mentioned in the last year of this decade Lane Fox organized his first public display of artefacts at the Museum of Practical Geology when the Ethnological Society met there four times according to Chapman, 1981.

Publications during the 1860s

Fox, A.H. Lane 1861. 'On a Model illustrating the parabolic theory of projection for ranges in vacuo' Journal of the United Services Institution 5 [1861] 497-501

Fox, A.H. Lane 1866 ‘On Objects of the Roman period found at great depth in the vicinity of the old London Wall’Archaeological Journal 24 [1866] pp. 61-64

Fox, A.H. Lane 1866 ‘Account of a human heart in a case found in Christ’s Church, Cork’. Archaeological Journal 24 [1866] pp. 71-72

Fox, A.H. Lane 1866 ‘On an ivory peg-top shaped object from Ireland’ Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in London 2dS 3 [1866] pp. 395-396

Fox, A.H. Lane 1867 ‘Roovesmore Fort, and stones inscribed with oghams, in the parish of Aglish, County Cork’Archaeological Journal 24 (1867) pp. 123-139

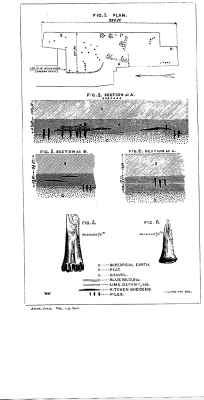

Fox, A.H. Lane 1867 'A description of certain piles found near London Wall and Southwark, possibly the remains of Pile Buildings' Journal of the Anthropological Society of London vol. 5 [1867] pp. lxxi-lxxxiii

Fox, A.H. Lane 1867 ‘Primitive Warfare. Parts I - III’. Journal of the Royal United Services Institution 11 [1867] pp. 612-43 and Journal of the Royal United Services Institution 12 [1868] pp. 399-439 and Journal of the Royal United Services Institution 13 [1868] pp. 509-539

Fox, A.H. Lane 1868 ‘Further Remarks on the Hill Forts of Sussex: Being an account of the excavations in the Forts of Cissbury and Highdown’. Archaeologia 42 [1868] pp. 53-76

Fox, A.H. Lane 1868 ‘On a Ring brooch from Lough Neagh, Ireland’. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in London 4 [1868] pp. 61-62

Fox, A.H. Lane 1868 ‘On a silver penannular brooch known as the Galway brooch’. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in London 4 [1868] pp. 141-143

Fox, A.H. Lane 1868 ‘On an Anglo-Saxon Sword from Battersea’. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in London 4 [1868] 143

Fox, A.H. Lane [and Tupper, AC] 1868 ‘On Two Rush-sticks from the Counties of Surrey and Sussex’. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in London 4 [1868] pp. 158-159

Fox, A.H. Lane 1869 ‘Flint Implements, found associated with Roman remains in Oxfordshire and the Isle of Thanet’.Journal of the Ethnological Society of London NS1 [1869] pp. 1-12

Fox, A.H. Lane 1869 ‘Note on a Gold Lunette, found near Middleton County Cork’ 1867. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in London 4 [1869] p. 195

Fox, A.H. Lane 1869 ‘Note on a Marble Armlet, Lukoja West Africa’. Journal of the Ethnological Society of London. NS1 [1869] pp. 35-36

Fox, A.H. Lane 1869 ‘On a Bronze Spear with a gold ferrule and a shaft of bog oak, from Lough Gur, County Limerick’.Journal of the Ethnological Society of London NS1 [1869] 36-8 also Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries in London 4 [1869] pp. pp. 195-196

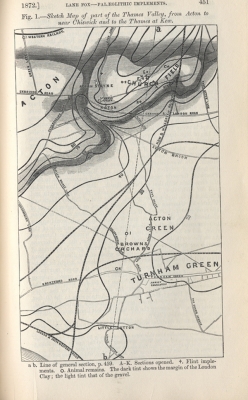

Fox, A.H. Lane 1869 ‘On the Discovery of Flint Implements of Palaeolithic type in the gravel of the Thames Valley at Acton and Ealing’. Report: British Association for the Advancement of Science [1869] pp. 130-132

Fox, A.H. Lane 1869 ‘Remarks on ... Westropp’s paper on cromlechs’ Journal of the Ethnological Society of London ns vol I pp. 56-67

Note that it must be assumed that the individual objects discussed in the publications above, all of which form part of the founding collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum, must have been in Lane Fox's ownership by the date on which he talked about them.

AP, February 2011.