To search the RPR site click here

Tylor himself is of course the best anthropologist in England and a very nice man indeed. [Walter Baldwin Spencer quoted in Mulvaney, 1985: 60]

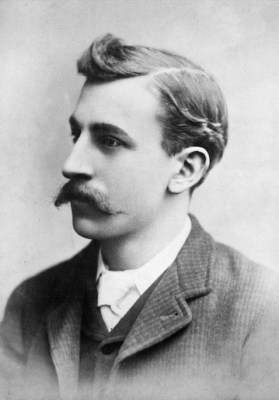

Edward Burnett Tylor (1832-1917) was five years younger than Pitt-Rivers, an English anthropologist who later in life became the first professor of anthropology in the UK at the University of Oxford. To find out more about Tylor visit his Dictionary of National Biography entry here.

Pitt-Rivers and Edward Burnett Tylor knew each other from at least the 1860s. They were colleagues, belonging to and serving together on the committees of several learned societies most particularly the Anthropological Institute. As this article makes clear, Pitt-Rivers was also able to use his influence to further Tylor's professional career leading to him being the first man to take an anthropological teaching post in an English university.

It is not known when Pitt-Rivers and E.B. Tylor first met. Following the Australian Aboriginal cricket tour of 1868 (see Mulvaney, 1967), Tylor corresponded with Pitt-Rivers about the flight of the boomerang:

10 Upper Phillimore Gardens - Dec 19 1869

Dear Mr Tylor

I put off writing to you in hopes of finding time to go into my views about the Boomerangs more in detail but as there seems to be little chance of that I may as well by a ??? what I have to say on the subject in a few words. There appears to me to long too much focus on the return flight of the boomerang, which is very useless and as far as I can learn but seldom Practical. I am told they will kill a bird sitting at a few yards distance by NEXT PAGE a direct throw and amongst a large flock of birds in the air it can be made to fly about in all directions with the chance of hitting something but as to hitting an object behind the back of what use would it be. The only difference between the Australian boomerangs and that of the ?Kolis is that the former is about 1/16 or 1/4 inch thinner and therefore lighter which causes it to fly about. But Jim Walter Elliot tells me the Kolis use it for larger game than the Australians and he has seen them break the leg of a tiger with it. To do that they must of course use a heavier weapon. In all other respects except NEXT PAGE weight and thickness the two weapons are identical both in respect to form and manner of throwing. It does not appear to me natural to expect that after so long separation the weapon of the two races should be perfectly identical, but they resemble each other more than most weapons which are known to be allied. What for instance can be more different in the mode of using than the club spear and paddle club throughout the Polynesian and Melanesian Islands are allied forms. Mr Bouwick tells me the Tasmanians used their spears as paddles and could not be induced to use any thing else. NEXT PAGE

It certainly is a mistake to suppose that the flight of the boomerang depends on its being flat on one side and convex on the other, or that the twist is necessary. When they have those forms no doubt its flight is affected by them but the majority have neither twist nor flat side and I have ascertained by practising with a perfectly flat one that it is not necessary. As to calculating the flight of the boomerang which I am told some German Author pretends to have done. It may be all very well as a mathematical exercise but quite impossible to apply. I believe no two boomerangs will fly quite alike nor will the same boomerang (after touching the ground as they make them often do) fly twice in the same direction. NEXT PAGE

(f.30) The Australians who exhibited their forms in the country last year [1] threw the boomerang. They fell in all parts of the field and many were lost by falling amongst the crowd. When therefore you consider the uselessness of the return flight - which is the point in which the two weapons differ, and on the the other hand the advantages of rotation, of the curve as facilitating rotation, of throwing the weapon point first to overcome the resistance of the atmosphere which are points in which they resemble each other I think I NEXT PAGE am justifies in saying that the resemblances are greater that the differences and thus the differences are no greater than might be naturally expected suggesting the weapon to have had a common origin and to have survived amongst races which have been countless ages separated from one another.

I am afraid this is not very intelligable or easy to read.

Yours very truly

A Lane Fox

I forgot to mention that of course the Indian War Quoit does not return being too heavy in proportion to its flat surface. I imagine however that if it would be got to fly far enough it would wind round as the boomerang sometimes does by reason of the greater resistance of the atmosphere on the side which is opposed rotation - as represented below.

Diagram of flying Indian War Quoit![A.H. Lane Fox to Tylor, 19 December 1869; British Library manuscripts Add. 50254 f.28-30]

See here for more information about Pitt-Rivers' research into boomerangs.

In 1872 Tylor became interested in the very fashionable pursuit of spiritualism. As Tylor himself explains:

‘In November 1872, I went up to London to look into the alleged manifestations. My previous connexion with the subject had been mostly by way of tracing its ethnology and I had commented somewhat severely on the absurdities shown by examining the published evidence. ...’ [unpublished ms in PRM ms collections, quoted in Stocking, 1971: 91]

Rather unexpectedly (for us, in hindsight) one of the people Tylor met during this investigation was Pitt-Rivers. On 18 November 1872, Tylor records:

[I heard of Mrs Basset[t] [a medium] once from another witness and] 'once from Col. Lane Fox, who was with his wife at a séance at Lady Powlett's. When the phosphoric lights came, Mrs L-F let go Mrs Crookes' hand, jumped up & caught the light & a very human hand[,] which struggled out of her grasp, which of course in the elaborate Medium report became a spirit-hand. Mrs L-F has not I think cared much for the business since. [Stocking, 1971: 97]

In 1872-3 Pitt-Rivers and Tylor collaborated with other members of the British Association for the Advancement of Science [BAAS] to prepare 'Notes and Queries', guidance for travellers (and later professional anthropologists) on what anthropological data and artefacts to collect during their travels.

It seems clear that Tylor must have visited Pitt-Rivers in his home before 1874 as he remarks in the Dictionary of National Biography entry for Pitt-Rivers that he wrote that, Pitt-Rivers 'collected weapons until they lined the walls of his London house from cellar to attic'.

Tylor was a key figure in arranging for Pitt-Rivers to be elected as a fellow of the Royal Society in 1875 and had personally written to Charles Darwin asking him to support the application:

Guildford Surry [sic] - Jan 29th 1875

Dear Mr Tylor

I forgot to mention when you asked me the other day about my literary or scientific performances such as they are that, not being either a literary or scientific man and the greater part of my life having been dedicated to my profession it might be perhaps as well if you think anything that I NEXT PAGE have done worth mention to quote you from the Royal Commission on the Subject of Military Education the passage which the Commissioners allude to my services in originating the School of Musketry at Hythe. As the school of Musketry has been of very wide special benefit to the army it is no doubt a matter which the Royal Society might fairly recognise. But should you do so it is right I should tell you exactly how far, as a military officer, I am able to state my claims on this head. As a matter NEXT PAGE of fact the School of Musketry was founded entirely on my reports to Lord Hardinge then Commander in Chief, and on the system introduced by me as a regimental subaltern and which were brought to Lord Hardinge's notice. When the school was established I was named Chief Instructor and the first official code of instructions was written entirely by me. But it is not the custom, on grounds of discipline, for officers to claim or receive the credit as author of any work which is adapted NEXT PAGE as part of the Regulations of the army, even when written entirely by them, and therefore it would not be proper for me to speak of myself as the author of any military official book, tho it is pretty well known by military men. All I can do is to quote any official acknowledgements that may be vouchsafed to me. The acknowledgement of the Royal Commission is in the "Second Report of the Royal Commission appointed to inquire into the present state of Military Education 1870", and is as NEXT PAGE follows, page XLI "We have also been favoured with the valuable evidence of Colonel Lane Fox, the officer to whom the origination of the School of Musketry was mainly due, and who was detailed by the late Viscount Harding when Commander in Chief to draw up the code of instruction which was first instructed into the ??."

I mention this as you naturally think as I do that NEXT PAGE my Anthropological contributions to Science alone do not afford my very weighty claim to recognition. Even tho you were kind enough to suggest to me to become a candidate for the Society. My School of Musketry work however was the result of many years hard work including experiments in connection with the small arms commission at Woolwich & Hythe and the Translation of some of the official NEXT PAGE codes of foreign countries.

I can send you the Report of the Commission if you like to see it but should like to have it back again as it is out of print and is important to me.

Yours sincerely

A Lane Fox

[Lane Fox to Tylor, 9 January 1875; British Library manuscripts Add. 50254 f.84: Charles Darwin to Tylor, 28 January 1875; British Library manuscripts Add. 50254 f.81]

It was in 1875 that Tylor had his first formal connection with the University of Oxford when he was awarded a DCL. Tylor was a Quaker who had been disbarred from taking part in English university life until the University Tests Act of 1871, when Nonconformists became eligible for Oxford fellowships. Tylor had tried to secure a post for himself in Oxford in the early 1880s through his contacts with Max Müller and George Rolleston. [Larson, 2008: 88; F. Max Müller to Tylor, 8 November 1881; British Library manuscripts Add. 50254 f.166, draft of letter from Tylor to Müller Add. 50254 f.120] Indeed, Rolleston was a further connection between the two men as he was a friend and colleague of Pitt-Rivers. In February 1881 the Tylors and Pitt-Rivers meet together in Oxford [University of California, Tylor papers]

In 1881 during his address as retiring president of the Anthropological Institute Tylor said:

In now resigning this chair to an already tried and successful President, General Pitt-Rivers, it may not be inappropriate for me to express a hope that his Museum of Weapons, which illustrates so many problems in his History of Civilisation, and has been already in its collector's hands so fertile a source of new ideas, may in some shape become a national institution. It is not a small duplicate of the national ethnographic collection of the British Museum, but something of different nature and different use. It is not so much a collection as a set of object-lessons in the development of culture, and the student whose mind is unprepared to visit intelligently the British Museum collection, may gain by preliminary study of the Pitt-Rivers collection an idea of development which will be a natural framework for further knowledge. He will know better what to look for in the vast galleries of the British Museum, and how to appreciate its meaning when he sees it...'

Tylor was invited to lecture in Oxford in November 1882 by twenty prominent fellows of the University, including several heads of college, led by Müller. [2] He delivered the lectures in early 1883, and was almost immediately appointed Keeper of the University Museum, following the recent death of the previous incumbent Henry Smith. Simultaneously, negotiations were taking place between Pitt-Rivers and the University of Oxford regarding the donation of his collection. In a letter Tylor wrote to Pitt-Rivers in September 1882, Tylor suggested that this donation might aid his own efforts to secure a permanent appointment in Oxford:

'I think I could do more effective work in such a position than anywhere else, whilst there is work left in me'. [Tylor to Pitt-Rivers, 24 September 1882, Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, Pitt Rivers papers L.8]

Following a series of letters discussing how Tylor's lectures should describe Pitt-Rivers' collection, Tylor received an enigmatic letter from Pitt-Rivers in June 1883 which suggested:

I have made a different proposal to Oxford which I think will please all parties and promote the advancement of the cause' [Pitt-Rivers to Tylor, 19 June 1883; British Library manuscripts Add. 50254 f.141]

It was at this time that Pitt-Rivers inserted a clause into the Deed of Gift of his collection to the University of Oxford, specifying that 'a Lecturer shall be appointed ... who shall yearly give Lectures at Oxford on Anthropology'. Tylor was duly appointed to his post, and so was intimately acquainted with the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford from its establishment in 1884. It was Tylor and Henry Nottidge Moseley who were responsible for the practical aspects of transferring the Pitt-Rivers collection from London to Oxford, employing Walter Baldwin Spencer (Moseley's assistant) to carry out the work. He later wrote to Balfour of this time:

.... I was much interested in your lecture to the Somersetshire Society more especially because it was the old Pitt Rivers collection that first gave me my real interest in Anthropology. It was I think in 1884 or 5 that Moseley asked me if I would spend the vacation in helping to pack up the collection which was then housed at South Kensington. I did a great deal of the packing up and it was intensely interesting to have Moseley and Tylor coming in and hear them talking about things. I remember well that Moseley seemed to know a great deal more than Tylor in regard to detail and of course after his experience on the ‘Challenger’ he could speak of many things with first hand knowledge but Tylor with his curious way which you may remember of every now and then as it were ‘drawing in his breath’—I don’t know how otherwise to express it—simply fascinated me. It was intensely interesting to a young man like myself and also a great privilege to come into such personal contact with two such workers. Of the two it struck me at that time that Moseley had the greater technical knowledge but Tylor the wider outlook. [PRM Archives, Spencer papers, Box IV: letter 21, 24 September 1920]

In 1886, Tylor purchased an artefact Pitt-Rivers wanted from the Oxford cattle market. (Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum Pitt-Rivers papers, L193]

In September 1888 the Tylors and Pitt-Rivers met up when they all attended the BAAS meeting in Bath. Anna Tylor records in her diary that the Tylors, Mrs Evans (presumably Mrs John Evans), the 'Pitt Riverses' and the Lubbocks went to the Roman Baths on Thursday 6 September 1888. A week later, from 13-15 September the Tylors stayed with Pitt-Rivers at his home at Rushmore, Anna's diary reporting much social visiting to local friends and society. The visit culminated in a 'large dinner - & band in the gallery in the evening' on Saturday 15 September.

It may be that during this visit that Tylor and Pitt-Rivers discussed the need for a guide to the Oxford displays at the Pitt Rivers Museum, because on October 4 1888 Tylor wrote to Pitt-Rivers with proposals for a catalogue:

... If I remember rightly, I was beginning to speak to you about the idea of a 3d [i.e. threepenny] Guide to the Pitt Rivers Museum when something else intervened and the subject did not come up again. The idea arose from the old Strangers Guide to the University Museum being now out of print and the Delegates wishing me to make arrangements to get a new one into shape. As this would involve some pages about the Pitt-Rivers [sic] Museum, the possibility suggested itself of these pages being also issued separately for visitors. The space (perhaps 10 - 15 pages 8vo) would be too limited for anything of the nature of a Catalogue but a ground-plan might be given with directions to the stranger where to find some of the principal series. For instance, he might be informed that on entering, he would find in the Court Cases to right and left specimens illustrative of the development of fire-arms from the matchlocks to the wheel-flint, and percussion types. Further to the left, he would come to the wall-case showing the development of the shield from the parrying-stick, and of metal armour from ... [sic illegible] defensive coverings. When he gets this information, the large labels on the cases, so far as Balfour has done them, will tell him more about the meaning of the series. When Balfour returns I will let you know, and I feel sure that your going over the Series with him will promote their being arranged so as to be open to the public (I mean those in the Galleries.) You will be able to ascertain from him what prospect there is of the publication of a Catalogue. To me it seems distant from the amount of work involved and the cost of illustrations. I think your active cooperation would do more than anything else to push it forward. ... P.S. I have just seen Balfour returned from Finland and looking forward to your visit. [Tylor to Pitt Rivers, October 4 1888, L.541 S&SWM, P-R papers]

At the end of the same month, on October 23, Henry Balfour and Pitt-Rivers dined with the Tylors in Oxford.

On 30 April 1891 Pitt-Rivers gave the only formal lecture he presented at the University of Oxford (the closest event that the Pitt Rivers Museum had to an opening ceremony) entitled 'The Original Collection of the Pitt-Rivers Museum: its principles of arrangement and history in the 'Museum Theatre' of the University Museum. On the same day he took afternoon tea with the Tylors at their home in the University Museum House (at the back of the University Museum, close to the Pitt Rivers Museum). He met them again on 16 December 1891 when the Tylors attended the address Pitt-Rivers gave to the Society of Arts.

On Saturday 3 June 1893 Pitt-Rivers came to lunch with the Tylors and Henry Balfour after 'an explosion in the Chemical Wing' (the two events are presumably unconnected) according to Anna's diary. In August 1894 Pitt-Rivers attended the BAAS meeting in Oxford and met the Tylors for dinner on 11, 13 and 14 August.

In 1897 Tylor wrote to Pitt-Rivers:

I am sorry to hear of your having been out of health of late, but at any rate you manage to keep up your work, which is the greatest of consolations. I speak feelingly having had a long and severe illness last year and though better now, finding work no longer easy. In writing about the kopis series I had better not trust to memory, but in a week or two I shall be back in Oxford and will go over them with Balfour. My impression is that the series is much or altogether on the original lines, and that the drawings go with the specimens. No doubt the geographical continuity in such series is as important as it would be to a zoologist. Indeed the problem which most occupies me is to trace inventions etc from their geographical origins, especially because ideas and customs are so apt to follow the same tracks. In working out the whole course of culture, it seems to me that to follow the diffusion of such a thing as a special weapon, is to lay down the main lines of the whole process, so that I should be among those most interested in the travelling of the Kopis. [Tylor to Pitt Rivers April 13 1897, L1788 Salisbury and South Wiltshire Pitt Rivers papers]

In 1898 Pitt-Rivers reflected on the collection at Oxford and his relationship with Oxford and Tylor

I hardly think that the system [Pitt-Rivers' own system of typological arrangement] has been favourably tried at Oxford. Mr Tylor and Mr Balfour have done their best no doubt, but they do not have the means, the materials, or the funds to work the system thoroughly, and as I soon found out that it was quite impossible that a method communicated by one person should be worked out effectively by others. Some of the series have not been developed at all, and others very imperfectly. the whole collection was out of sight for a long time, five years, I think, whilst the building was being erected, and my health has not allowed me to go there much since. It is not the kind of a building for a developmental collection, which would be better in low long galleries well lighted from above and without pretention; the large and lofty space was not wanted. Rolleston and Moseley were the heads when I gave the collection to Oxford, and Tylor though the best man possible for Sociology, had at that time but little knowledge of the material arts. Balfour, though hard-working, does not, I believe know fully to this day what the original design of the collection was in some cases. I do not however complain of the men. They have done their best to carry out an idea which was an original one at the time, and circumstances have been against it. Oxford was not the place for it, and I should never have sent it there if I had not been ill at the time and anxious to find a resting place for it of some kind in the future. I have always regretted it, and my new museum at Farnham, Dorset, represents my views on the subject much better. I shall write a paper about it before long if I live ...’ [Pitt-Rivers to F.W. Rudler 23 May 1898, Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum Pitt Rivers papers, quoted in Chapman, 1981: 535]

However, it is clear that Pitt-Rivers had himself changed his mind about some aspects of the founding collection:

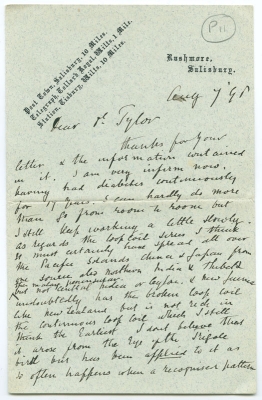

‘I have rather changed my view as to the principle on which a small collection for a local anthropological museum, such as my present one is, should be collected. I still think the primary arrangement should be in divisions by arts and subjects and the secondary one within each large division should be geographical. But the primary divisions in a small local Museum should be broader, thus instead of having a separate division for representations of the human form I make it Art and Ornament and make it include both realism and styleism and also the adaption of animal forms to ornament which in my original collection I kept separate. Where sequences occur they can be shewn within the primary division and where a reference passes from one country to another the geographical sub-arrangement must be slightly broken.’ [Extract from letter from Pitt Rivers to Tylor, PRM Archives P11, dated 7.8.1898]

Pitt-Rivers also remarks of another new collection he was making:

I have been making a very good collection of the Benin bronze castings. The best I believe out of the B[ritish] M[useum]. They are extremely interesting as shewing a phase of art of which there is no actual record. I cannot quite make out whether the ... [lost wax] process came from Portugal. It does not follow that because European figures are occasionally represented that it all came from Europe. Most of the forms are indigenous ... [Extract from letter from Pitt Rivers to Tylor, PRM Archives P11, 7.8.1898]

showing that Tylor and Pitt-Rivers had continued to exchange information and views throughout their lives.

As has already been shown above, Pitt-Rivers and Tylor socialised together as well as conferred about their work, indeed they socialised with their wives as a party which must indicate a fairly close acquaintance. It is worth noting however, that they addressed each other fairly formally, see the page from a letter from Pitt-Rivers illustrating this page which shows Pitt-Rivers addressed Tylor (at least in letters) as 'Dr Tylor'.

Not only did they invite each other to stay in their homes, but they also met at other social events. Anna Tylor's diaries (now held at the University of California) record a whole series of social events of which the following are a sample

- Thursday 22 February 1882. Edward and Anna meet Mrs Horace Davey and Mrs Pitt-Rivers 'at home' ...

- Tuesday 27 March 1882. Anna 'up to town' with Edward, 'Adventures in the City, saw Alfred ... Genl. Pitt Rivers's and the Bradleys'

- Saturday 2 June 1883. Anna came to Oxford where she had 'Mr and Mrs Fearon ... & the Pitt Riverss

- 3-16 August 1885, on holiday in Scotland with the Pitt-Rivers family, on the 3rd the Tylors '...met with the Pitt Riverss & made plans with them to go to Stornoway', on the 16th after travelling around they 'parted from the Pitt Riverss' in the evening, although they later met up again at Strathpeffer on 22nd August where they dined and stayed together (presumably in a hotel). [See here for more information about this time]

- Thursday 1 July 1886, 'The Pitt Rivers's came to see the Museum ...'

Anna Tylor seems to have been friendly with Mrs Pitt-Rivers, Anna's diary often noting lunches together.

Tylor and Pitt-Rivers' friendship continued until Pitt-Rivers' death in 1900, Tylor attended his funeral at Tollard Royal on Pitt-Rivers' country estate. E.B. Tylor also made significant contributions to the Pitt Rivers Museum at Oxford, see here for more information about his own collections.

In 1953 the Anthropological Society of Oxford held a special meeting to celebrate anthropology at Oxford. At the meeting John Linton Myres (nearing the end of his very long and active life at Oxford) gave his impressions of Pitt-Rivers and the Museum:

‘... When Edward Harrison exhibited his ‘eoliths’ at the Royal Anthropological Institute, Tylor took me to the meeting as a visitor. We dined with the ‘Pagans’ at Pagani’s in Great Portland Street. Sir John Evans was very scornful of ‘eoliths’: cynical persons said that Harrison had not given him any. Pitt Rivers welcomed them, showing how they were fitted to the hand, and how the flaking resulted from use. His demonstrations were very bad for his malacca cane. Tylor himself was cautious in approval. It was a lively evening.... [Myres, 1953: 5-6]

Ollie Douglas, AP and Chris Wingfield, April 2011.

Notes

[1] Presumably a reference to the Aboriginal cricket tour of 1868

[2] The invitees were H.W. Acland, J.F. Bright, G.C. Brodrick, I. Bywater, H.W. Chandler, G.W. Kitchin, M.A. Lawson, H.G. Liddell, W. Markby, D.B. Monro, H.N. Moseley, W. Odling, H.F. Pelham, J. Percival, J. Prestwich, A.H. Sayce, H.J.S. Smith, J.B. Thompson, J.O Westwood. See letter from Müller et al to E.B. Tylor, November 1882 British Library manuscripts Add. 50254 f.121]

Bibliography for this article

Brown, Alison, Jeremy Coote and Chris Gosden 2000 'Tylor’s Tongue: Material Culture, Evidence and Social Networks'. Journal of the Anthropological Society of Oxford 31(3):257–276.

Chapman, William Ryan 1981. ‘Ethnology in the Museum: A.H.L.F. Pitt Rivers (1827–1900) and the Institutional Foundations of British Anthropology’, University of Oxford: D.Phil. thesis.

Gosden, Chris, Frances Larson and Alison Petch 2007 'Origins and survivals—Tylor, Balfour and the Pitt Rivers Museum and their Role within Anthropology in Oxford 1883–1905'. In A History of Anthropology at the University of Oxford. Peter Rivière ed. Oxford, U.K.:Berghahn.

Larson, F. 2008. 'Anthropological Landscaping: General Pitt Rivers, the Ashmolean, the University Museum and the shaping of an Oxford discipline' Journal of the History of Collecting, vol. 20, no. 1. pp. 85-100

Mulvaney, D.J. 1967 Cricket Walkabout ... London: Cambridge University Press

Petch, Alison. 2007 'Notes and Queries and the Pitt Rivers Museum' Museum Anthropology vol30 no. 1 Spring 2007: pp. 21-39

Stocking, G.W. Jnr. 1971 'Animism in theory and practice: E.B. Tylor's unpublished notes on "Spiritualism"' Man, n.s, vol. 6 no. 1 (March) pp. 88-104

Wingfield, C. 2011 'Is the heart at home? E.B. Tylor's collections from Somerset' Journal of Museum Ethnography no 22 (December 2009) pp. 22-38

Note: Transcriptions of letters from Pitt-Rivers to Tylor held in the British Library by Chris Wingfield, transcriptions of University of California diaries of Anna Tylor by Ollie Douglas.

![E.B. Tylor [1998.267.88]](../../component/joomgallery/1998_267_88_20101102_1565609643-view=image&format=raw&type=img&id=489&Itemid=41.jpg)