To search the RPR site click here

Peter Rivière

Introduction

Pitt-Rivers put his vast collections together from numerous sources, and this series of articles examines some of those sources. It deals with the objects obtained from temporary exhibitions, mostly those held in London; from his own collecting activities while travelling in the United Kingdom, Europe and further afield; by donation, and by his reliance on auction houses and dealers. It is intended as an introduction and overview and as such it should provide a starting point for any researcher or other person interested in investigating Pitt-Rivers’ collecting habits. Information about his career, his activities year-by-year, and his colleagues and associates may be found elsewhere on this website; that about the auctioneers and dealers is appended to this series of articles. Accordingly only limited detail is provided about such matters.

The division into five sources has been done simply for ease of exposition. In practice, the way in which a particular item was acquired was often less clear cut. For example, Pitt-Rivers whilst travelling in the United Kingdom or abroad, purchased many objects from local dealers. Such objects are listed as being obtained both by field collecting and from dealers.

The quality of the documentation is an all-important factor in this survey. That for the Second Collection is much fuller than that for the Founding Collection, and this point has to be made on more than one occasion below. We quite simply do not know how very many of the objects the latter contains came into Pitt-Rivers’ possession, thus any comparison between the two collections needs to be treated with caution. At the same time, while never poor, he was a very rich man after he inherited his cousin’s estate in 1880. From that date on he was able to gratify his interest more-or-less at will.

The price paid for objects has often been recorded in the documentation of the Second Collection. Examples of these are given, and where they are an equivalent in today’s monetary value is provided in parentheses. Here the currency conversion table provided by the National Archives has been used to convert the 19th century cost into modern value. (http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/currency/results.asp#mid) The rates are provided for ten-year intervals, so that, for example, the conversion rate for 1880 has been used for the years from 1876-1885. This does result in some in some apparently odd results – for example, £20 in 1885 converts to £966 (using the 1880 rate), whereas £18 in 1886 is £1,078 (using the 1890 rate). Such conversions are notoriously difficult and there are a number of different ways that can be used for computing the figures which in turn give radically different figures. For example, a suit of armour Pitt-Rivers bought in 1887 cost him £60, which the National Archives table converts into £3,593. Another site, www.measuringworth.com, gives £4,940 using the retail price index or £31,600 using average earnings.

I. Exhibitions

In that part of the collection that ended up in the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, the Founding Collection, it is possible to identify just 33 items which had been obtained from exhibitions. It is likely that there are more than these but the quality of the documentation does not allow us to know this. Given Pitt-Rivers’ involvement in the development of a rifle for British military use the first item obtained from an exhibition was, appropriately enough, a rifle. However, the information about it on the database is not consistent. The item in question, a French Chassepot rifle, is said to have been procured from the 1851 Great Exhibition but it is also stated that this weapon was not invented until the 1860s. Of the 33 objects, the majority (22) are listed as coming from the 1871 Sind Exhibition, about which no information has yet been found. Furthermore there is some doubt about whether all 22 do come from this source, for, as is indicated on the database, six of them may have come from Paris. It is noticeable that all of the latter are musical instrument (drums and a lute), whereas those simply listed as from the Sind Exhibition are pottery of some sort. There is one further item, an Indian drum, which is definitely listed as coming from Paris. It is likely that all these musical instruments came from the 1867 Paris Exposition Universelle or second Paris World Fair, as did a Japanese trumpet which is down as coming from that exhibition. It is known that Lane Fox attended the 1878 Paris Exposition Universelle with one of his daughters [see the letter to George Rolleston, Ashmolean Museum which starts 'Gulldford, Monday] To these are to be added a further seven assorted items (three French bronze coins, a bronze needle and part of a lute, and two Chinese copper coins) which came from the 1878 Paris Exposition Universelle, the third Paris World Fair. Finally there is a Norwegian model boat that was obtained from the 1883 Great International Fisheries Exhibition (about which more below). This would appear to have been made by Lysenkappen Mikkel of Alverströmmen and is object 32 (p.309) of the official catalogue. [1]

Because the documentation of the material which constituted Pitt-Rivers’ Second Collection is much fuller, we know far more about its sources, and are able to identify a number of exhibitions from which objects were obtained. First there is the Great International Fisheries Exhibition just referred to. It was held at South Kensington in the garden of the Royal Horticultural Society, then in Exhibition Road. It was a large affair, opened on 12 May with considerable pageantry by the Prince of Wales who substituted for Queen Victoria at the last moment. It ran until 31 October and was visited by over two million people. [2]

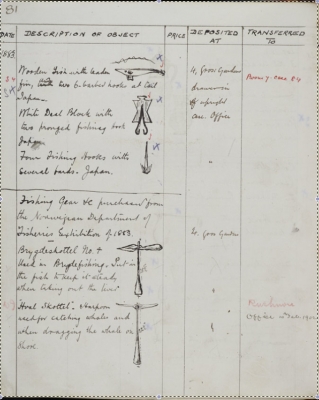

The Norwegian sector of the exhibition was large with exhibits in almost every class. The Norwegian model boat mentioned above was only one of 18 Norwegian items obtained at this exhibition, but the only one that went to Oxford; probably because it formed part of a series on modes of navigation. The others items were sent to Wiltshire. [3] They are all equipment for whaling or brygde (Cetorhinus maximus, the Basking shark) fishing. In the case of the latter many of the items have to do with the removal of the liver which constitutes up to 25% of the body mass and consists of 60-75% oil. An entry under Norway in the Official Catalogue (p.326 ) contains a description of the use of many of these items. A further 12 items are from Japan; they are an anchor and assorted fishhooks and their weights. The Japanese section (p. 268) at the exhibition was very small. For none of these items, whether Norwegian or Japanese, is a price given, although it is noted that all items were purchased at the exhibition. It is stated in the regulations of the exhibition that exhibitors are requested to mark the selling price of articles and that objects sold cannot be removed until the end of the exhibition.

The exhibition from which Pitt-Rivers obtained the most objects was the Colonial and Indian Exhibition of 1886 which was held at South Kensington.[4] The exhibition was opened on 4 May by Queen Victoria who was also its patroness. She paid at least two further visits to the exhibition in order to examine the displays under more normal conditions. Displays included, as well as artefacts, people from various parts of the world and large illustrations showing scenery of fauna, and flora. The exhibition received much press attention; The Times devoting many column inches to the opening ceremony, making it the subject of editorials, and running articles on various aspects, such as the art of India, throughout its duration. It proved extremely popular and more than five and a half million people, over 33,000 a day with 81,000 on August Bank Holiday, visited it before it closed on 10 November.

Although The Times listed people associated with the organization of the exhibition and eminent visitors, there is no mention of Pitt-Rivers in connection with it. Given that he was a central figure in the world of ethnographic collections, this is surprising. Even so the Second Collection contained 382 objects from the exhibition, these coming from at least 16 different countries. There was a bulky official catalogue to the whole exhibition, [5] but most countries or colonies produced their own as well. It might be noted, however, that the entries in the Official Catalogue do not always accord exactly with the information given in the individual catalogues. Reference will be made to the specific country catalogues below but it may be noted that they vary greatly in the amount of detail they contain on specific objects and thus how far objects acquired by Pitt-Rivers can be identified in them. In many cases the description in the exhibition catalogue has been copied into the catalogue of the Second Collection, although some interesting detail has sometimes been left out. The intention here is to give indications of the sort of identifications possible so that those with a particular interest can follow them up.

It is not clear how the display objects were dispersed at the end of the exhibition but we know that many objects were for sale. In fact, in certain catalogues the prices of the exhibits were given, and with reference to the Hong Kong section, it is stated in the Official Catalogue (p. 357) ‘Note – In connection with the Hong Kong Court is a shop or bazaar, in the balcony of the Royal Albert Hall, for the sale of Hong Kong articles, presided over by Chinese’. In some cases exhibits went to public auction after the Exhibition closed, as advertisements by Stevens Auction room for a sale of Chinese objects from Hong Kong on 14 December, and of Indian material by Christie’s on 13 January 1887 witness. [6]

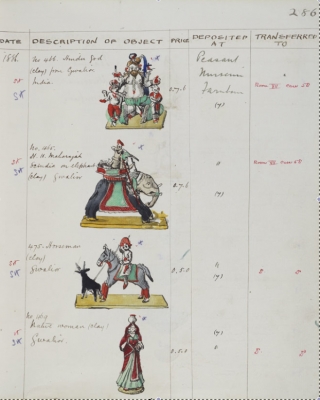

The country from which most exhibits were acquired, over a quarter of the objects, was India with 110 items to which may be added a further five objects which are listed in the database as coming from Bangladesh (although it did not exist at the time). There are no objects entered as from Pakistan. The Indian section of the exhibition was very lavish with a replica of an Indian palace and the different regions each having their own court and often ‘real’ people. [7] Objects of the Tribal peoples together with models of them were displayed separately in what are referred to as sub-courts. The items acquired by Pitt-Rivers come from different regions of India, from Karnataka in the south, to Gujarat and Rajasthan in the northwest, to Orissa and Bengal in the east. The very detailed catalogue produced makes it possible to identify quite a lot of the objects in the Second Collection or, at least, the region they come from. [8] Furthermore, all those objects on pp. 284-90 in the Second Collection catalogue Volume 2, have their exhibition catalogue number included. The majority of the items, 69, fall into the pottery class, consisting of plates, cups, jugs, lamps, and figures of people and animals. There are 19 models made from painted plaster including 10 models of poisonous snakes, officially used to identify those that should be killed. [9] Two exceptionally expensive items were obtained from Myanmar, then Burma and ruled from India. They are a silver bowl costing £100 (£5,989) and a silver gilt cup costing £18.5s (£1,093). Interestingly enough neither item was put on display but handed over to the butler at Rushmore House for safekeeping. Information in the database explicitly states in many cases that the item was ‘purchased’, ‘bought’ or ‘obtained’ at the exhibition, and in nearly two-thirds of the cases a price is given.

As well as the objects from India there are 26 items from Sri Lanka, mainly masks and ornaments. [10] The Sri Lankan catalogue is one of those that explicitly states whether an object is for sale or not, and where it is a price is given. For example, the Buddhist Ola book (2:275/2) is almost certainly to be found in Section 4 of the Sri Lankan catalogue (p.117) where it is described as ‘Old blank book with elaborately chased silver covers’ and priced at £30 (£1,797). The 13 masks which Pitt-Rivers acquired came from a display of 38 such objects in the ‘Ethnology’ section and what are described as ‘Painted tiles’ in the Second Collection catalogue are almost certainly the objects referred to as ‘Painted plaques’ on p.106-7. Maldives Islands are included with Sri Lanka but are only represented by a single object, a firestick. This was donated to Pitt-Rivers by James Hayward. Little is known about Hayward except for the fact that he was in charge of the gems in the Ceylon section of the Exhibition. [11]

The African continent was the source of 69 items. The majority of these, 41, came from Southern Africa, of which 25 were from Basutoland, now Lesotho, and were collected by Colonel Clarke, the British Resident at Maseru.[12] There is no dominating theme to the collection although 25% of the objects are classed as pottery and there are numerous pipes. The three walking sticks that are just listed in the database as African almost certainly came from Southern Africa, as such objects are listed in the exhibition catalogue. The 28 other African objects come from West Africa,[13] six of the objects (two whips and four brass figures) have no further geographical identification. There are 18 items from Sierra Leone, of which 13 are made out of plant fibre, seven of these being grass mats. There is also a chief’s robe which cost six guineas (£377) and is the only item from Africa for which a price is recorded. Finally, there is a single object from Cameroon, a model canoe, which is readily identifiable in the exhibition catalogue on p.13.

Cyprus with 56 objects is next best represented. These are all connected with peasant agricultural or manufactures, and a very large number of them can be readily identified in the exhibition catalogue. [14] Among the latter was a loom for weaving silk, and three women and two men had been brought from Cyprus in order to demonstrate the technique. Interestingly enough it is noted in the catalogue that the fund set up to bring these Cypriots to London was under the auspices of the ‘Sir R Biddulph’. This was probably General Sir Robert Biddulph of the Royal Artillery, who had served in the Crimean War (as did Pitt-Rivers) and was High Commissioner for Cyprus 1879-86. If, as seems likely, he was acquainted with Pitt-Rivers this may account for the large number of items from a relatively insignificant colony.

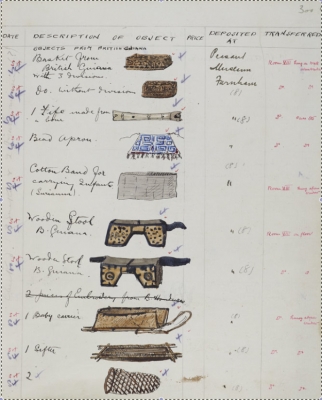

The West Indies provided 36 objects, coming from a number of different islands, although interestingly there is nothing from either Jamaica or Trinidad. It is possible to identify from the catalogue many of the items obtained. [15] Antigua is best represented with 12 objects, followed by Barbados with eight, Dominica and St Vincent with five each, St Kitts and Montserrat with two and St Lucia with one. Finally there is one object from an unidentified island. Pottery objects dominate with 25 out of the 36 objects described as pots, but there are also four models, three of them different sorts of carts from Barbados and one an arrowroot grinder from Antigua. A price is listed for six of the objects, four pots from Antigua for 1s 6d (£4.49p) and two pots from St Kitts at 2s 6d each (£7.49p). From the same part of the world, Guyana (then British Guiana), there are 15 objects. It is clear from the catalogue of the British Guiana section [16] that all these objects come from the section entitled ‘Ethnology’ and are undoubtedly of Amerindian origin, although from which of the indigenous groups it is not specified. They include two stools, a woman’s bead apron, and various bits of basketwork including a cassava squeezer, described as a cassava strainer and then mistakenly entered as a beer strainer in Pitt Rivers’ catalogue. None of the Guyana collection is priced.

The 14 items Pitt Rivers acquired from Canada are all from First Nation Peoples. The country’s catalogue is often unspecific, using such general descriptions as ‘Indian Fancy Work’, which makes it hard to identify specific objects. [17] The Haida of the Northwest Coast provided 13 of the items including two totem poles carved from soapstone figures which are identifiable as item 1353 on p.242. The one object not from the Haida is a fine Blackfoot tomahawk. With two exceptions prices are given for the Haida objects and range from 5s (£15) for a mortar to £5 (£299) for a model totem pole. Interestingly all the Haida objects are described as ‘Bt of Hyda London’ which might suggest that the sale was made direct to Pitt-Rivers or his agent by the Haida themselves, although there is no mention of Haida attending the exhibition.

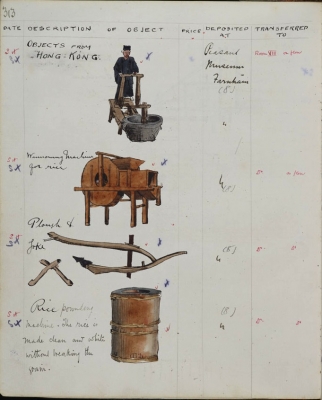

From Malta came 12 objects, consisting of two sets of six elaborate silver buttons or clothes fastenings. The catalogue [18] indicates that several sets of buttons were on exhibition so it is difficult to identify them exactly but Exhibit 401 (p.15) is a strong candidate; it consists of 12 buttons, ‘silver, pear-shaped’, described as found on ‘costume of Maltese countryman’ and priced at £1.14s (£102). A collection of eight agricultural items, a plough, a harrow, a rake, a yoke, threshing machine, rice pounder, mill etc., came from British North Borneo, today Sabah and part of Malaysia. Although a Handbook to the territory was published [19] it has not been possible to trace a copy of it; that held by the British Library was destroyed in the Second World War. There is, however, a section in the Official Catalogue devoted to the colony which includes a list of exhibits (pp. 362-5). Here many of the objects obtained can be identified as being from the Dusun. There are 17 objects from Hong Kong; ten of them are agricultural tools, six Chinese brass locks and one a clothes iron. The colony does not appear to have published a separate catalogue but its entry in the Official Catalogueis to be found on pp. 356-7. It has been noted above that there was a shop at the Exhibition selling Hong Kong articles and later an auction of the exhibits, but it is not known whether Pitt-Rivers obtained his objects through either of these channels.

Finally there are 11 miscellaneous objects, three gourds, a basket, a piece of embroidery and a couple of nails, of which not even the continent of origin is known. It might be noted, however, that they all appear together on the same page (p.306) of volume 2 of the Second Collection, and the impression is that they are objects which have become separated from the group to which they belonged and have been lumped together at the end. One might also note the surprising absence of any objects from Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific region.

In a very high proportion of the cases, the date at which Pitt-Rivers acquired the objects is given as October, and sometime more precisely as 1 October. This was before the exhibition closed on 11 November so it is not clear how the mechanism by which he procured these items worked since it suggests that they were removed while the exhibition was still open.

Contemporaneous with the Colonial and Indian Exhibition was the Ceylon Exhibition held at the Royal Agricultural Hall during July 1886. The Times, which refers to it as Hagenbeck’s great Ceylon show, described it as ‘instructive and amusing’. [20] Indeed it seems to have been more like a travelling circus with elephants, dancers, snake-charmers, conjurors and musicians. There was an accompanying display of Sinhalese objects, mainly agricultural implements. Pitt-Rivers obtained 28 items, ranging from pots to tools to model carts. Of the 18 items for which a price is given the most expensive was one of the last at £1.10s (£90), and there were two large decorated pots at a £1 each (£60).

Between 1887 and 1891 Earl’s Court played host to a series of national exhibitions. [21] The first of these was American which was dominated by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. Pitt-Rivers did not acquire any objects at this exhibition. The following year, 1888, the Italian Exhibition of Fine Arts opened on 14 May with Earl’s Court turned into a replica of the Coliseum. Although two catalogues were published, one listing fine art and the other more general items, it has not so far been possible to track down copies of them. [22] Pitt-Rivers acquired 19 items from the exhibition. Seven of these are described as modern Italian pottery and no price is given; eight are further pottery objects with the most expensive 16s (£48). The most interesting items are two mosaic pictures of the Madonna and Child and two tapestries, one of the Madonna and Child signed by Erulo Eroli. The former cost £8.10s each (£509) and the latter £38 (£2,276) for both. All four items were bought from the artist and sculpture Luigi Gallandt who was responsible for the two mosaics. [23]

In 1889 Earl’s Court staged a Spanish Exhibition which opened on 1 June. The Times gave it a half-hearted review, commenting that, except in the picture section, there were not many exhibits and there was no catalogue by the time of opening. [24] Pitt-Rivers acquired 28 items from the exhibition. Of these 17 are pottery objects, bowls, jugs, etc., and ten gilded silver sconces. No price is given for the pottery items, whereas the sconces cost £2.2s.4d (£127) in total.

A French Exhibition was mounted at Earl’s Court in 1890 but nothing was obtained from it by Pitt-Rivers. Then in 1891 it was home to a German Exhibition, opening on 9 May that year. The Times noted that unlike the previous exhibitions there was less emphasis on the spectacular and more on Germany’s industry, art and science. [25] No catalogue to this exhibition has been traced. Pitt-Rivers obtained from it 16 glass goblets, all made by the Moser Glass factory of Carlsbad (Karlovy Vary) and costing £8 (£479) for the set.

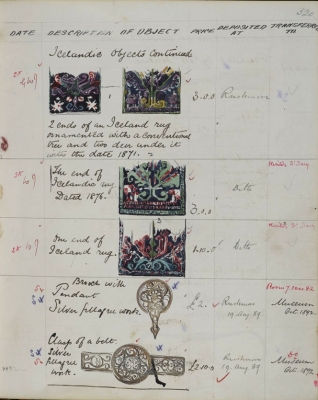

In the same year as the Spanish Exhibition there was an exhibition of Icelandic objects at the Royal Archaeological Institute in Oxford Street. This exhibition had been organized by a Mrs Magnusson and was under the patronage of the Prince of Wales. Its aim was to raise money for the education of women in Iceland. Pitt-Rivers bought 38 objects including ornaments, carpets, animal harness, domestic utensils and boxes for various purposes. There is a price recorded for almost every object, the most expensive being a saddle for £10 (£599) although most items cost less than a pound. Also at the Royal Archaeological Institute that year Flinders Petrie had an exhibition of his Egyptian finds, of which Pitt-Rivers purchased 35. The price of which is not recorded.

The Empire of India Exhibition was held at Earl’s Court in 1895 and according to The Times was immensely popular with ‘enormous crowds’ flocking to it on Whit Monday.[26] The Pitt-Rivers’ collection acquired from it five items. These were three marble inlaid vessels, a model of a carving on the gate of the Taj Mahal, and a lacquer vessel from Mynamar. The prices are given and all the objects are listed as having been bought from London Exhibitions Ltd. This company had been responsible for exploiting the Earl’s Court area and became Earl’s Court Ltd early in the 20th century. [27] Then there are three further Indian objects (three figures), also acquired from London Exhibitions Ltd, in 1897 which are also likely to have come from the Empire of India Exhibition although this is not stated. This was the last exhibition from which Pitt-Rivers made acquisitions. In great part this can be attributed to a decline in the number of exhibitions between 1895 and 1900 that were suitable for making the sort of acquisitions that Pitt-Rivers appeared to favour.

Given the very large number of objects that went into Pitt-Rivers’ collection in the last 20 years of his life, the total acquired from exhibitions is relatively insignificant. Even so, the question remains, why did he buy what he did at exhibitions? The answer to that question is in most cases far from clear. Some acquisitions would appear to be additions to an existing collection. For example the 16 goblets that were purchased from Moser Glass factory at the German Exhibition of 1891 may well have been to complement the 180 pieces of glass acquired from the same manufacturer in 1886. Likewise the Ancient Egyptian material bought at Flinders Petrie’s 1889 exhibition might be seen as purposefully adding to the numerous Egyptian objects acquired earlier in the decade. Otherwise explanations for particular choices are much harder to come by, especially when it is possible to see from the catalogues what else he might have acquired. In other words it is not possible to reach any conclusion on why he chose the objects he did rather than some others. What one can say is that pottery objects dominate the acquisitions, and this is true whether the objects come from the colonies or western nations. Of the 382 objects purchased at the Colonial and Indian exhibition 111 are classified as pottery, while at the Italian Exhibition 15 of the 19 items are pottery and at the Spanish 17 out of 28. However, the class of pottery covers a wide range of actual objects including vessels, cups, jugs, plates, bowls, lamps and figures. No other class of objects comes close to this, the nearest being tools, mainly agricultural or domestic, which form the majority in collections from two of the exhibitions, Ceylon 1886 and Egypt 1889. After that it is difficult to identify any particular pattern or emphasis in the acquisitions from exhibitions although, it should perhaps be repeated that overall exhibitions were not an important source of objects for Pitt-Rivers.

Notes

1 See International Fisheries Exhibition 1883. Official Catalogue. William Clowes & Sons, London 1884.

2 The Times contained a large number of reports on the exhibition and The Illustrated London News various illustrations. For full details of the exhibits, see Official Catalogue.

3 Wiltshire is here used to refer to Rushmore House, King John’s House or the Farnham Museum.

4 This exhibition was a good source of artefacts for many museums and collectors, for example A.W. Franks also bought extensively from it for the British Museum [see Caygill and Cherry, 1997 'A.W. Franks ...' page 140-1][footnote added by Alison Petch]

5 Colonial and Indian Exhibition, 1886. Official Catalogue. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

6 Most of this information is derived from The Times digital archive.

7 For some idea of what it was like, see John Dinsdale, Sketches at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition. Jordinson & Co., London 1886. There are four views of the Indian section.

8 Empire of India. Special Catalogue of Exhibits by the Government of India and Private Exhibitors. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

9 The catalogue states: These models are used in district offices for the identification of those poisonous snakes for the destruction of which rewards are offered by the Government. This is a detail that was not copied into the Second Collection catalogue.

10 Illustrated Handbook & Catalogue for Ceylon. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

11 The Times, 19 July 1886.

12 Catalogue of the Exhibits of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope. Richards, Glenville & Co, London 1886.

13 Handbook of the West African Coast. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

14 Handbook to Cyprus and Catalogue of the Exhibits. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

15 Handbook and Catalogue. The West Indies and British Honduras. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

16 Colonial and Indian Exhibition, 1886. Special Catalogue of Exhibits in British Guiana Court. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

17 Official Catalogue of the Canadian Section. McCorquodale & Co., London 1886.

18 The Malta Court. Catalogue of the objects exhibited at the London Exhibition of 1886. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

19 Handbook of British North Borneo. William Clowes & Sons, London 1886.

20 The Times, 22 July 1886.

21 For a full account of these exhibitions, see Charles Lowe, Four National Exhibitions in London and their Organiser. T Fisher Unwin, London 1892.

22 Italian Exhibition. Catalogue of Fine Art Department. Waterlow & Sons, London 1888, and The Italian Exhibition (Official Catalogue, exclusive of fine art department). Waterlow & Sons, London 1888. The British Library catalogue lists both these titles but they were both destroyed by enemy action in the Second World War.

23 Erulo Eroli (1854-1916) was an Italian artist and tapestry maker. Luigi Gallandt was a 19th century Italian sculptor about whom no biographical details have so far been discovered.

24 The Times, 3 June 1889. It is not known if a catalogue was produced as one has not been found. On the other hand Darbyshire’s Guide to the Spanish Exhibition, London 1889 contains only general information.

25 The Times, 9 May 1891.

26 The Times, 4 June 1895.

27 For a brief history of Earl’s Court, see www.eco.co.uk/p/earls-court/21.

II. Field Collections

Pitt-Rivers, when he travelled in the United Kingdom or overseas, took his enthusiasm for collecting with him. We can be fairly certain of this because where we have information on his movements we can often trace an increase in objects coming from the places he visited. This is far more difficult with reference to the Founding Collection since we rarely have any definite dates as to when certain objects were acquired. Even so it is possible even with reference to his collection in the Pitt Rivers Museum to tell that he collected where he went. It is far easier with the Second Collection, because both dates and places of acquisition are more frequently recorded, and because the activities and movements of Pitt-Rivers himself are much better known for the later part of his life.

As far as archaeological finds are concerned, the objects are mainly those which resulted from Pitt-Rivers’ own excavations or those of other people with which he was associated to some degree. This is not the case with regard to ethnological objects as their collection did not usually involve field collecting in the usual sense of the term for Pitt-Rivers never conducted any ethnographic field research. He may have on occasion obtained items directly from those who actually made and used them but more often he seems to have acquired them from dealers in the locality. In other words, for the purpose of this survey, the notion of ‘field collecting’ is used in a fairly loose way.

Of the 19,397 objects listed on the database of the Founding Collection Pitt-Rivers is recorded as being the field collector of 5,034. Not surprisingly the vast majority of these, 4,471 items, were collected in England, with a further 87 from Northern Ireland and 34 from Wales. Pitt-Rivers does not appear to have undertaken any field collecting in Scotland prior to 1884. These figures can be broken down even further. Of the objects collected in England 4,461 are classified as archaeological, of which 2,919 are of pottery, 1,094 of stone, 232 of bone and 129 of some sort of metal. It is also possible to relate them to Pitt-Rivers’ archaeological activities. For example, there are 171 objects from London Wall found during digging foundations for buildings in 1866, and 131 from Acton in 1869. After that year, he undertook some sort of archaeological investigation almost every year up until 1880 in some part of the country. The best represented counties are Sussex with 2,922 items from a series of excavations, 672 from Kent, 134 from Surrey, 130 from Yorkshire, and 122 from Oxfordshire. Most of the 34 objects from Wales come from the excavation of two cairns at Moel Faban, Penrhyn Castle, near Bangor, in 1868 or 1869. Of the 87 objects from Northern Ireland, 71 come from County Antrim, where he is known to have been in 1864. Seven of the 11 objects from the UK which are unambiguously classified as ethnological are firearms or their accessories and collected in 1852 when Pitt-Rivers was a member of the committee charged with deciding which rifle the British army should adopt.

When we look overseas we find Pitt-Rivers involved in the Crimea War in 1854. He travelled there via Malta and Bulgaria. The Founding Collection contains 17 items from Malta but there is no way of knowing whether he collected them and if so whether in 1854 or when he was stationed there in 1855-57. This is equally true of the 13 objects, all silver ornaments, from Bulgaria. We can, however, be rather more certain about the 27 Russian military objects, swords, guns, helmets, etc., all associated with the Crimea War – it is highly probable that Pitt-Rivers obtained these during his service in the war.

In 1858 he holidayed in Austria, but there is no evidence he did any field collecting on this visit as the 28 objects recorded as having been collected by him in that country were acquired by him in 1882 when he spent several months there and in Germany. In the latter country he collected 10 items. It is noticeable that of the 38 objects collected 27 are classed as locks.

There are 1,383 objects in the Founding Collection recorded as coming from France, of which Pitt-Rivers is listed as being the field collector of 303 items, 286 of them defined as archaeological and all but four of stone. All these objects were probably obtained during his time in France in 1878-9. For example, the 192 objects, including 17 ethnological objects, from Brittany were probably collected by Pitt-Rivers when he visited there in October-November 1878 and March-April 1879. In the latter year he was also in the Pas-de-Calais where 94 items were collected by him. There are a further 16 items listed as collected in Normandy, and it is possible that these were also collected in 1879, although it must be stressed that we cannot be absolutely certain when any of the objects from France were collected.

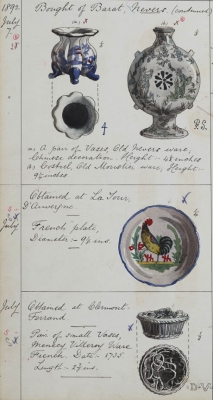

As well as the objects for which Pitt-Rivers is listed as the field collector, there are a number of other items from France which he possibly collected in person. For example, he visited France, Belgium and the Piedmont in 1852, in order to study musketry training in those countries, and there are some firearms in the Founding Collection from those countries that might have been collected during that tour. There are 81 objects, 65 of them classified as ethnological, from the Auvergne region of France, none of them entered as having been collected by Pitt-Rivers. Even so it is known he was there in 1860, but it is more likely that they were a later acquisition as there are entries of objects from that region in the accessions book for August and September 1880. It is recorded that Pitt-Rivers was in Paris in the latter month, but there is no evidence that he also went to the Auvergne at that time. If he had, which is not out of the question, then we can probably regard him as the field collector of these items.

It is impossible to tell whether any of the 572 objects from Canada in the Founding Collection were collected by Pitt-Rivers during the months he spent there in 1861-62; it seems likely but the documentation provides no evidence. Disappointingly this is also broadly true of Ireland where Pitt-Rivers was based at Cork between 1863 and 1866. Only 39 of some 566 items are identified as having been collected or probably collected by Pitt-Rivers. If this is narrowed down to the region round Cork, we find that there are 55 objects, four of which, three of them human remains, were collected directly by Pitt-Rivers. On the other hand a large number of these items were clearly obtained from local people – for example, a John Windele was the previous owner of 12 of them and the collector of ten of them.

In the summer of 1879 Pitt-Rivers, together with George Rolleston, Oxford’s Linacre Professor of Anatomy, made a trip to Denmark and Sweden, collecting 28 archaeological items in the former country, and 12, mainly ethnological, in the latter. The journey may have extended to Norway as the accessions book contains entries of nine objects from that country in November the same year.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that Pitt-Rivers was the field collector of more objects than the 5,034 items from the Founding Collection that are so recorded, but the documentation does not allow us to be certain. Even so Pitt-Rivers’ field collecting accounted for roughly a quarter of the Founding Collection. It is also noteworthy that 4,963 of these objects are defined as archaeological items, leaving only 71 listed as definitely ethnological items. This also contrasts with the classification of objects from the whole of the Founding Collection which is almost equally divided between archaeological and ethnological objects. Perhaps most importantly it indicates just how actively Pitt-Rivers was participating in archaeological investigations prior to 1880.

When we turn to the Second Collection a rather different picture emerges. First there are far fewer items in the Second Collection for which Pitt-Rivers is recorded as field collector. The total is only 728, approximately one-seventh the number contributed to the Founding Collection although the size of the two collections is roughly similar, 19,397 for the Founding against 20,217 for the Second Collection. Finally, before turning to the details, we might note that while the Second Collection is also roughly equally divided between archaeological and ethnological items, about two-thirds of the objects collected in the field by Pitt-Rivers are classified as ethnological against one-third archaeological.

Once again it is the United Kingdom with 213 objects that is the major focus of Pitt-Rivers’ field collecting. Of these, 119 items are from England, and 79 of them archaeological finds from his famous excavations in Wiltshire. The remaining 40 objects are readily associated with Pitt-Rivers’ movements and activities in the country; for example, the three objects from excavations at Hunsbury Hill, Northamptonshire in 1883 or the six from Cumbria which arose from his visit to the region in 1885. He does not appear to have visited Northern Ireland after 1880 and there are just three items from Wales, all pieces of stone from sites that Pitt-Rivers went to inspect in his official capacity as Inspector of Ancient Monuments in 1885. There are 90 items from Scotland and in contrast to England the vast majority, 80, are ethnological objects. The objects were collected during a series of trips to Scotland in 1883, 1885, and 1886. Those from 1883, about one-third of the number, were purchased from a dealer in Edinburgh, but in the latter years, when he visited more remote parts of the country, his field collecting is closer to what the term might suggest.

When we look at Pitt-Rivers’ field collecting outside the United Kingdom, we may note that a few items from his visit to Scandinavia in 1879, already mentioned, ended up in the Second Collection. These were three Swedish brooches and a stone axe from Denmark; it would appear that these items were rather more valuable than the objects that went to the Pitt Rivers Museum which mainly consist of horse shoes and harness, and stones used as chessmen.

In February and March 1881, the year following his inheritance of the Rushmore estate, he travelled, under the auspices of Thomas Cook, to Egypt. He met the famous Egyptologist Flinders Petrie there and made a small collection of 30 items of which over two-thirds were Ancient Egyptian. This, however, may well underestimate the number of items that he collected as the pages in Volume 1 of the Catalogue of the Second Collection (pp.22-28) where the entries crediting Pitt-Rivers as the field collector are to be found include a further 28 Ancient Egyptian objects of which the field collector is listed as ‘unknown’. It may also be noted that his visit to Egypt appeared to have created in Pitt-Rivers a particular interest in Ancient Egyptian material. The Founding Collection only contains 125 such objects whereas there are 956 in the Second Collection.

It was, however, Pitt-Rivers’ visit to Germany, Austria and the modern day Czech Republic (then Bohemia and part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) in 1882, which resulted in one of his largest field collections. The exact days he was holidaying in those countries is not known but he appears to have been there in part of July and September, and the whole of August. It is not clear how he assembled his collections, although he certainly bought objects from what appear to be dealers and he also obtained some items from the Musée central romain-germain in Mainz. There are 156 objects from Germany, 141 from Austria and 116 from the Czech Republic, making a total of 413 (although because some of the objects are entered as coming from more than one country the real figure is slightly lower than that). There is an emphasis on rural and peasant domestic and agricultural objects, but by no means exclusively so; for example, there are six silver salt cellars and spoons from Karlovy Vary (Carlsbad), the Czech Republic and 16 swords from the museum in Mainz.

Pitt-Rivers returned to Austria in 1886, but on that occasion, with the exception of a single object, a peasant’s lunch canteen, he obtained no further objects. This could be explained by the fact that he was in poor health and at Carlsbad for treatment. In July and August1892, he was in the Auvergne and collected 30 items, all classified as ethnological and ranging from a bedstead to a roof tile. This journey was the last Pitt-Rivers made abroad.

Even if the term field collecting is used in a very loose sense, this activity played a relatively minor role in the accumulation of Pitt-Rivers’ Second Collection, certainly much less than for the Founding Collection. The main reason for this is almost certainly that very little of the large amount of archaeological material that emerged from his excavations round Rushmore, which were his main archaeological interest in the last 20 years of his life, ended up in his Second Collection. For some unknown reason Pitt-Rivers did not choose to document the objects found during the excavations on his estate in the catalogue volumes now in the Cambridge University Library. It is not known, at the present time, if they were listed in some other form of documentation. Some of them at least were clearly displayed at one time in his museum at Farnham, and in the second half of the twentieth century they were transferred to the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum where they remain.

Although what archaeological excavations produce is to some extent chance, one can see in Pitt-Rivers’ field collecting of ethnological items his ideas about what he wanted his museum at Farnham to portray. He set out his ideas on this in 1891; briefly his aim was to interest the local agricultural community by exhibiting a range of historically and culturally diverse objects of the sort with which it would be familiar (for his own words, see here). This undoubtedly accounts for the emphasis on peasant and domestic objects that characterise his field collecting practice. Furthermore the results of his local archaeological investigations were revealed more by models of his various excavations than finds, which must have been of greater interest to the local population at whom the exhibitions were aimed.

III. Donations

Pitt-Rivers depended for a part of his collections on donations from a wide range of people. Unfortunately the documentation of the Founding Collection does not record how the vast majority of the objects came into his hands. The identity of a previous or other owner is often given but this says nothing about the nature of the transaction, although it is quite possible that many of the objects were donated. An example of which there is record is the gift of 215 stone tools from Patagonia by the author and ornithologist William Henry Hudson. Probably best known for his romantic novel Green Mansions, made into a film starring Audrey Hepburn, Hudson was brought up in Argentina and moved to England in 1874, the year in which his gift was made. On the other hand information about how Pitt-Rivers came by objects is often, if not always, recorded in the catalogues of the Second Collection, and it is probably safe to assume that those who were donors of items to that collection were also donors to the Founding Collection. If that is the case the people involved were almost entirely Pitt-Rivers’ scientific colleagues. John Evans, the archaeologist, gave 37 assorted stone and bone prehistoric tools; Augustus Wollaston Franks, Keeper of British and Mediaeval Antiquities at the British Museum, four objects including Australian and Javanese spears; Edward Tylor various illustrations of firearms; William Matthew Flinders Petrie, the Egyptologist, three objects from Ancient Egypt; Henry Nottidge Moseley, Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Oxford and influential in setting up the Pitt Rivers Museum, gave 13 objects, most of them collected on the HMS Challenger expedition of 1872-6; Richard Burton, the explorer, gave 66 objects including an assortment of South American objects and 44 sherds from Istria; John Lubbock gave 16 objects, mainly stone tools from various parts of the world. Lubbock was later to become a member of the family as Pitt-Rivers’ son-in-law, and a donor to the Founding Collection who was not a scientific colleague but a member of the family was his third son, William Augustus Lane Fox-Pitt who was in the Grenadier Guards, served in the 1879 Zulu War and brought back 34 Zulu objects for his father’s collection.

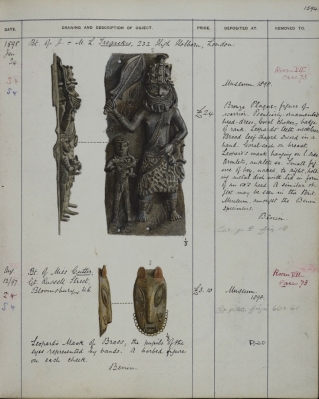

The database shows that 762 objects were donated to the Second Collection, although this is possibly an under-recording. There are 86 different people listed as donors, but only 15 of those gave ten items or more, whereas 29 gave only a single object. The donor of the largest number of objects, 165, was Sir Arthur Charles Hamilton Gordon (1829-1912) in 1882. There is, however, some doubt about the exact number that remained in the Second Collection as it is noted in the catalogue that not all the objects illustrated there were retained and Gordon took some back. Gordon was the son of the fourth Earl of Aberdeen, and at different periods in his life was the Governor of Fiji, New Zealand and Ceylon. He was created the first Baron Stanmore in 1893. All but five of the objects came from his time in Fiji (1875-80), and clubs dominate the collection, forming almost two-thirds of it. The second largest donation was by John Henry Rivett-Carnac and John Cockburn around 1883. It consists of 131 stone tools from the Northwest Provinces of India. Colonel John Rivett-Carnac (1838-1923) was a member of the Indian Civil Service, a fellow of a number of antiquarian societies and published on Indian antiquities. Little information has been found on Cockburn, other than that he was interested in archaeology and published accounts of his work in India in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute.

There is some doubt about the next donor, Francis Rogers Hiscock or his son Frank. The former was a tenant farmer of Pitt-Rivers, working Rookery Farm next door to the Larmer Tree, and so presumably was his son. The Second Collection has 70 items associated with them, but only three of these are definitely listed as donations. These three, a decanter, a goblet and a tinderbox, are relatively recent, whereas the other 67, which may or may not have been donations, are all stone tools found at different times during the 1890s.

After that the size of donations falls off. The next two largest donors are people who contributed to the Founding Collection. In 1884 Richard Burton presented 36 stone tools from West Africa which he had presumably collected while consul at Fernando Po between 1861 and 1864. The next largest is 35 objects from Flinders Petrie (1853-1942), the Egyptologist, who presented a collection of Pre-dynastic pots and a stone tool in 1895.

A son-in-law, Sir Walter Grove, probably gave the 32 assorted objects that he had bought in The Netherlands, although they are not entered as donations. The Billington family gave 23 objects between 1892 and 1895. The donors were the Rev. George Billington, Miss Billington and Horace Billington, all of Chalbury Rectory, Horton, near Wimborne in Dorset. The objects come from all over the world, West Africa, India, Nepal, Tibet, North America, and even one from Chalbury; the last being a glass bottle unearthed by a gravedigger. A number of the objects given by Miss Billington, all from India, had been collected by John Rivett-Carnac. Someone called Mrs Liarmouth (probably Learmonth) of Hanford, Dorset, gave 20 objects, comprising two sets of arrows in 1896, one from Afghanistan and the other from the Solomon Islands. In 1896 a Mr Keller, about whom nothing has been found out, presented 19 Roman objects excavated near Bad Homburg, Germany. Augustus Wollaston Franks, whom we have already noted as a donor to the Founding Collection, Keeper of British and Mediaeval Antiquities at the British Museum, gave 17 items; two of these were Japanese pottery objects and the other 15 flint implements from Le Moustier, France. In 1895, Lady Blackett of Ropley, Alresford, Hampshire, gave 15 Zulu bead ornaments. Nothing is known about Lady Blackett but there is an outside chance she was the wife of Major-General Sir Edward Blackett who served in the Crimea War and thus may have been known to Pitt-Rivers. She may also have been related to Mary Netta Blackett, the wife of Pitt-Rivers’ son, Lionel.

The Rev. Cecil Vincent Goddard of various parishes in Dorset and Wiltshire gave 15 assorted items over a number of years (1887-95) from a range of different countries, mainly Switzerland but including Mexico, Trinidad, Canary Islands, and Italy. However, these donations are only a small part of the 83 items in Pitt-Rivers’ Second Collection obtained from Goddard; the other 68 items were either on loan or purchased. Pitt-Rivers and Goddard appear to have had a complex association, more about which can be read here. There are also 339 objects in the Pitt Rivers Museum collected by Goddard, but these do not form part of the Founding Collection as they were added to the collections between 1892 and 1931.

A similar situation seems to have held with George Fabian Lawrence, a dealer of Wandsworth, London, from whom Pitt-Rivers acquired 1,806 objects, 13 of which, for some reason, perhaps oversight, he was not charged. There is a small collection of 12 objects, mainly Palaeolithic stone tools, given by a James Ralls, an ironmonger in Bridport and amateur archaeologist, who was probably their excavator. Finally, there are ten ‘peasant toys’ from Venice purchased by Miss Laura Russell of Audley Square, London and presented to Pitt-Rivers in 1889. It would appear that these items were not too carefully looked after as they are variously described as ‘broken in pieces’, ‘decayed’, and ‘missing’. These were, however, not the only objects that failed to be cared for; a Kashmiri woollen cap given in 1895 by a neighbour of Pitt-Rivers, a Captain Cartwright of Sixpenny Handley, was described by 1899 as ‘entirely destroyed by moth’.

Perhaps the striking thing about these 15 donors is that they mostly have known connections with Pitt-Rivers of some sort. There those such as Burton, Franks, Petrie, and Rivett-Carnac whom he would have known through his involvement in the scientific world; Gordon and Blackett in a military context; and the Billington family, Ralls and perhaps Goddard who were country neighbours, although the last entered into a sort of commercial relationship with Pitt-Rivers, as had Lawrence.

When we look at the people who donated fewer than ten items, the same pattern emerges. For example, there are those who have already been mentioned as donors to the Founding Collection: the archaeologist John Evans gave eight assorted locks and keys; Henry Moseley, Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Oxford, gave a pair of lamps from France; John Lubbock six stone tools from Pakistan and an opium pipe from Japan. Other donors from the scientific world were H Pressland who gave two items from excavations at Hunsbury Camp, Northamptonshire with which Pitt-Rivers was associated; L’École de Anthropologie de Paris five spindlewhorls from the Pyrenees; Émile Cartailhac, the French archaeologist, gave him a reproduction of a figure carved from reindeer horn; William Cunnington, a well known Wiltshire archaeologist, and possibly his son Edward, gave a variety of objects from local excavations and one object each from Mexico, Peru and West Africa; Salomon Reinach, a French archaeologist at the National Museum of Antiquities, St Germain-en-Laye, gave seven plaster casts of prehistoric objects; Patrick Geddes, Professor of Biology at University College Dundee, gave five objects from Cyprus which he collected whilst there in 1896 helping with refugees from the Turkish-Armenian war; Henry Ling Roth, museum curator, gave five objects from Nigeria and sold Pitt-Rivers two others. They had been collected by his brother, Felix, who had been medical officer on the Benin punitive expedition of 1897; Frederick James who had been Pitt-Rivers’ assistant for ten years before moving to the Maidstone Museum gave a jug; Henry Willett, a founder of the Brighton Museum, gave a baker’s tally stick from France;

A second class of donors are members of Pitt-Rivers’ family. Lubbock, as Pitt-Rivers’ son-in-law straddled the scientific and family association; Lady Stanley, who gave a Spanish jug in 1886, was his mother-in-law; St George Fox-Pitt, Pitt-Rivers’ second son; William Fox-Pitt, Pitt-Rivers’ third son, and his wife Lily; Lionel Fox-Pitt, the fourth son; Ursula Scott (née Fox-Pitt), his eldest daughter; the essayist and suffragette Geraldine Grove, another daughter, and Thomas, her brother-in-law, all gave the odd object, although no more than half-a-dozen. Already mentioned are the 32 Dutch objects acquired from Geraldine’s husband, Walter Grove, and although these are not listed as donated it seems likely that he would have given the items to his father-in-law.

Thirdly many local people, including some of Pitt-Rivers’ employees, also presented objects. Susan Chown, a kitchen maid at Rushmore, gave a piece of wood with a carved face, and Mr W Thomson, head gardener at Rushmore, a contemporary Norwegian jug. Alfred Seymour of Knoyle, Wiltshire and Liberal MP for Salisbury, and his wife Isabella gave three objects which they had collected in Algeria. Lady Baker, of Shroton and one of Pitt-Rivers’ tenants, gave a Roman tile she had found; Charles Bennett, another neighbour living on Cranborne Chase, gave a sundial; a local doctor, Thomas Smart, a key and a deer antler; another doctor, Humphrey Blackmore of Salisbury, one of the founders of the Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, gave two Palaeolithic stone axes; Walter Genge, a district surveyor from Shaftesbury, gave a horseshoe dug out of the road during repairs; Charles Hunt, a builder from Blandford, who gave an anti-witch charm, a bottle of urine found suspended upside down in a cottage chimney; John Carmichael, a plumber of Blandford, gave, appropriately enough, an iron pipe found in the ceiling of the Railway Inn; Thomas Gatehouse, a tailor of Tisbury, gave a sword; James Brown of Salisbury who may have been a butcher since four of the seven items he donated were associated with that occupation; the rector of Tollard Royal, George Waterfall, presented four objects, three old coins found locally and a padlock; another local vicar, Ernest Hasluck of Handley, presented rather more exotic items, a bow and arrows from the Amerindians of the Gran Chaco, Argentina, which suggests he may have been a missionary at one time; Thomas Beesley of Cheselbourne, Dorset, yet another clergyman, gave a mediaeval tile found in the vicarage; Mrs Best of Ludwell presented a stone arrowhead found when a watercress bed was being dug; Julia Forbes, another neighbour, gave two objects; Tom Jones, a farmer of Cranborne, gave five horseshoes and an unidentified object described as a ‘gypeiere’; a further three horseshoes came from Walter Fletcher who was the County Surveyor for Dorset and a friend of Thomas Hardy; and one further horseshoe came from James Madstone, about whom nothing is known; a Mrs Beaumont of Witchampton, Dorset, also about whom nothing more is known, gave seven objects collected in the West Indies. One suspects that in many of these cases the donor had come across, found, inherited or otherwise acquired objects that they did not know what to do with or no longer wanted and decided that Pitt-Rivers might like whatever it was.

Then there are a few who seem to have a partly commercial relationship with Pitt-Rivers. Frank Blanchard, an auctioneer in Blandford, gave a single item and sold Pitt-Rivers three others. This pattern was not that unusual as we have seen it above with regard to Lawrence and Goddard. Another example is A Kotin, a London dealer who specialised in Russian goods; he gave Pitt-Rivers two objects, pottery figures, and sold him a further 15, one, an enamel cup, for £35. Another London dealer, Frederick Litchfield, gave four items and sold 63 to Pitt-Rivers. It is not clear in these cases whether these objects were thrown in with those bought or through oversight they were not charged for.

Into a rather different category from any of the above, is Carter & Co of Poole Dorset, decorative art potters, which gave nine examples of their ware in 1895. Samples of their ware had originally been requested by Pitt-Rivers, but when the company learnt that the objects were to go on permanent display, they declined payment as their exhibition would act as an advertisement for the firm. [see here]

IV. Auction Houses

Important sources of objects for Pitt-Rivers were auction houses. He started buying from them early in his collecting career and made increasing use of them later in life. This was almost certainly because of his increased wealth, although the caveat should be repeated that the documentation of the Founding Collection often does not reveal the source of objects, nor is the cost ever recorded.

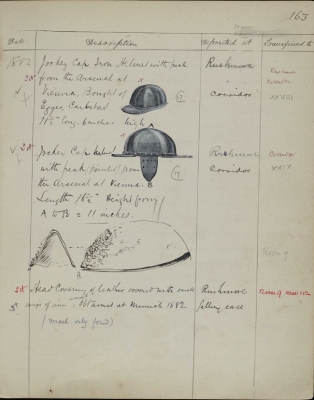

We know of only four auction houses at which objects for the Founding Collection were acquired. On 27 June 1862 Bullock of 211 High Holborn, London sold a collection of 116 objects which was certainly in the possession of Pitt-Rivers by 1868, although we have no definite evidence that Pitt-Rivers acquired it directly from the auctioneer. The firm had been founded by Edward Bullock in 1805 but he had died in 1840 so the firm was either being run by one of his descendants or, if no longer in the hands of the family, the name had been retained. The firm continued to exist into the next century but Pitt-Rivers does not appear to have made further acquisitions from it. The collection in question had been made by John Petherick in the Sudan between 1856 and 1858. Petherick was an engineer who also acted as British Vice-consul in Khartoum. The objects are mainly weapons, tools and ornaments from various Southern Sudanese groups such as the Bongo, Nuer, Dinka and Shilluk.

In 1870 Pitt-Rivers bought two Romano-British pottery vessels from Last of Shrewsbury, which had been found by an Edward Stanier in 1866. We know nothing about him but it is possible that he lived in Wroxeter, Salop, where the objects were found. This suggests that Pitt-Rivers was in Shrewsbury in 1870 although there is no other evidence that he was. We are no better informed about a collection of 40 objects from Oceania, mainly ornaments from the Solomon Islands that he bought from Davitt (or Daritt) in the late 1870s. Nothing is known about the firm; the objects appear to have been collected around 1876, but it is not known who the collector was.

The one auction house with which Pitt-Rivers dealt throughout his collecting life was Sotheby’s. His earliest purchase there, which is his first recorded acquisition at an auction house, was in 1861, when he bought two items, a set of bells from Burma and a xylophone from Africa, which had previously been in the Museum of the Royal United Services Institution. Then in 1868 he bought a Bronze Age cinerary pot from Ireland that had been collected by William Chadwick Neligan. Neligan was a priest in Cork and in 1878 Pitt-Rivers acquired a further 17 items at Sotheby’s which Neligan had owned.

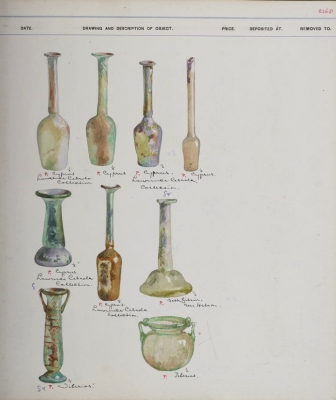

The main acquisition in the Founding Collection from Sotheby’s is 187 objects from the Cesnola collection. This was composed of objects collected by General Luigi Palma di Cesnola or his brother Alessandro, mainly on Cyprus; some of the material resulting from their own excavations on the island. Out of the collection 28 are listed as having been acquired by Pitt-Rivers in May and July 1871, and the remainder later in the 1870s, a few apparently as a result of re-sale including the objects collected by Neligan referred to above. There are a further three objects identified as being from the Cesnola collection that are not listed as bought at Sotheby’s, although it seems probable that they were. Luigi Palma di Cesnola was an Italian-American who was US consul on Cyprus in 1865-77, and later became Director of the Metropolitan Museum, New York.

In July 1879 Pitt-Rivers bought 72 objects that had originally belonged to James Medhurst; 67 of these are identified as Romano-British and of the other five, three are unidentified, one is described as Roman and one as Bronze Age. Medhurst’s collection resulted from excavations which he undertook near Weymouth, Dorset in 1843-6.

Whereas four auction houses were the sources of objects for the Founding Collection, this number grew to seven for the Second Collection, although only a handful of objects were obtained from five of them. Also, as mentioned above, during the latter part of his life Pitt-Rivers appears to have made more extensive use of auction houses in order to obtain objects. The extent to which this is so is demonstrated by Sotheby’s, the only auction house to figure in both lists. The number of purchases from Sotheby’s for the Second Collection added up to 3,395 items, or 4,130 objects, that is approximately one-fifth of the total collection.

It is not possible to review in detail all the objects obtained through Sotheby’s and a representative sample will have to suffice. Pitt-Rivers continued purchasing material from the Cesnola Collection, often in large quantities. On 1 June 1883 he bought 200 items, all from Cyprus. In the documentation of the Second Collection, the cost is often but not always given. On this occasion the most expensive object cost £3.12.0 (£174 in today’s money), but most no more than a few shillings. Then on 15 May 1884 he bought a further 120 items, mainly Cypriot pieces but also some from elsewhere around the Mediterranean. Very few prices are recorded from this sale. In March 1888 he bought a further 218 Cypriot objects. Once again most objects cost only a few shillings and by far the most expensive was a glass perfume container at £6.17.6 (£412). In 1892, a further 123 objects which had been collected by Alessandro Palma di Cesnola but had been in the collection of the late Edwin Lawrence were bought. Lawrence was a stockbroker and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, but, perhaps more important in this context, he was Palma di Cesnola’s father-in-law. Finally, there are a further nine items from the Cesnola Collection for which no date of acquisition is listed; these give a grand total of 661 items from the Cesnola Collection that Pitt-Rivers bought through Sotheby’s for the Second Collection.

Earlier, on 8 June 1882, he acquired ten fans that had been part of the collection of Robert Walker of Uffington, Oxfordshire. The total cost was £36.3s (£1,740), and individual fans ranged in price from 18s to £6.15s. Four days later, 12 June 1882, he spent a much larger sum (although we do not have the exact figure it was well in excess of £125 or £6,000 at today’s prices buying 153 objects of Ancient Egyptian provenance. Nor was he done with bidding for Ancient Egyptian material at Sotheby’s; he was back there to buy 13 items on 4 December 1882, and again on 10 March, 13 March, and 28 May 1883 buying respectively 95, 14 and 102 items. After this his enthusiasm for Ancient Egypt, which was almost certainly aroused by his visit to Egypt in 1881, seems to have waned slightly and he bought just a handful of such objects at sales in 1884, 1885, 1886, 1888 and 1895. It might be noted that Pitt-Rivers did not restrict his buying to Ancient Egyptian material on these occasions as he bought a further 34 objects from Sotheby’s from other Egyptian historical periods. Nor, on the occasions when he bought these Egyptian objects did he so restrict himself; for example on 4 December 1882 he also acquired a further 47 items which came from elsewhere in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean.

At an auction of arms and armour, the property of the late W J Bernhard Smith on 13 May 1884, Pitt-Rivers acquired 55 lots. We do not have prices for every object, but the total he paid for those we do amounted to £119.9s (£5,480). Two weeks later, on 26 May, he bought a further 138 items, this time from the collection of Frederick George Hilton Price. Price was a banker with a great interest in archaeology and antiquities. He put together a large collection which, after his death in 1909, formed the nucleus of the London Museum at Kensington Palace. Presumably, therefore, the sale in 1884 was of duplicate items or those that in some way did not fit into his collection. The items acquired by Pitt-Rivers are mainly from London, although there are two which were found on the site of the Angel Inn, on the High Street, Oxford. Again, later the same year, 4 July, he bought 60 assorted Greek and Roman objects found in Hungary.

In May 1885 Pitt-Rivers attended what would appear to be a clearance sale of the dealer Button; certainly it is described as ‘sale of English and Foreign China and other works of Art forming the entire stock of Mr Button of Regent Street’. His name in one entry is given as J Jackson Button and he appears to have had premises at 2 Pall Mall Place as well as in Regent Street. Pitt-Rivers bought 31 lots, 18 of which are lacking any sort of provenance and the other 13 came from various European countries. The objects themselves were a mixed assortment ranging from tea caddies, to needle cases in the shapes of animals to a Jewish circumcision knife. In July the same year Pitt-Rivers attended another sale of a dealer’s stock, this time that of Egger’s Antiquities. Samuel Egger, an Austro-Hungarian had an antiquities business in Budapest, and Pitt-Rivers had previously acquired an object from him in Carlsbad when he was there in 1882. On this occasion he bought 13 items of which five objects are identified as of Ancient Greek origin and three Roman. In 1891, Pitt-Rivers bought a far large number of items, 136 in total, at Sotheby’s that derived from Egger, who had died the previous year. The items acquired mainly consisted of weapons and ornaments, many from Hallstatt culture but also of Early Greek and Roman origin.

On 5 December 1885, he obtained from a sale of Greek and Roman antiquities at Sotheby’s 129 items, ranging from 20 spindle whorls for 5/- (£12) to a bronze and gold armlet for £20.10s (£990). It is not known whether he attended that sale in person, but we know that he sent an agent, William Talbot Ready, to another sale five days later who bought only a single item because prices were so high. Pitt-Rivers was back on 18 March 1886 to buy a further 77 objects from a sale of assorted antiquities, many of unknown provenance, including a double-headed bronze axe for £16.15s (£1,003), but including a few Ancient Egyptian items. Later in the same month, 30 March, he acquired further Ancient Egyptian objects from the collection of Lionel Moore, about whom nothing is known although he may have been a diplomat. On 29 June 1886 Pitt-Rivers bought 50 more objects at another sale of antiquities including a rare ‘Gaulish helmet’ for £49 (£2,934), a Roman glass vessel for £18.10s (£1,108), and a Tyrolean bronze knife for £16 (£958).

Sotheby’s did not do so well out of Pitt-Rivers in 1887, as he bought a mere three objects at its sales. In 1888, however, he was again active at its sales, buying 301 objects that year. In February he bought 13 objects that had been in the possession of William Neligan, the Irish priest mentioned above as Pitt-Rivers had purchased some of his objects from Sotheby’s for the Founding Collection. The following month he purchased the 218 Cypriot objects from the Cesnola collection also already mentioned, and in June 43 objects of Classical Mediterranean origin that had probably been owned by the Revd John Hamilton-Gray. He had died in 1867 but his widow, Elizabeth Caroline, had survived until 1887, her death having presumably led to the dispersion of their collection. He came from an old Scottish family and was a recognised scholar, as was his wife.

In May 1889, the coin collection of Charles Warne was auctioned, and Pitt-Rivers acquired 48 of them. Warne was a Dorsetshire antiquarian who had died in 1887. In November of the following year Pitt-Rivers successfully bid for 295 objects from W W Robinson’s collection. These are mainly stone tools and weapons but there are also 56 amber beads and a few bronze pieces; some the last proving expensive, one going for £45 (£2,695) and another for £41 (£2,455). We know next to nothing about Robinson other than he put together an extensive collection of archaeological and antiquarian objects.

The dispersal sale in May 1891 of the late William Edkins’ collection of old English pottery and Romano-British pieces was the source of 90 objects for the Second Collection. Edkins was a builder in Bristol who had a few years earlier donated some china and glass to the British Museum and the Victoria & Albert. The following month Pitt-Rivers acquired the objects from Samuel Eggers already mentioned. In 1892, as well as the objects from Lawrence/Cesnola collection also mentioned already, Pitt-Rivers bought 44 ancient pottery items from Europe, Peru and Mexico that had been part of George Vize’s collection. Not much is known about Vize; he may have been a boxer who lived in Holloway Road, London, but unusually this does not appear to have been a dispersal sale following death. Yet another dispersal sale consequent on death was of Henry Durden’s collection of coins, of which Pitt-Rivers acquired 97 early British and Roman coins. Henry Durden was a grocer of Blandford Forum, Dorset who established his own museum. Following his death his collections were sold by his son John in two tranches, in 1892 and in 1893. Pitt-Rivers appears not to have bought anything at the second sale.

In 1893, 133 objects were acquired from the collection of the late S D’Ehrenhoff. Little is known about D’Ehrenhoff, but the collection is mainly Ancient Greek material except for 24 wooden plinths of unknown provenance for which Pitt-Rivers paid a guinea (£63). At the same sale he acquired 39 mostly religious items, all European but otherwise of mainly unknown provenance. At two other sales in that year of the collections of William and Thomas Bateman he obtained 251 objects. These are antiquities from many parts of the world including Iran and Mexico, but mainly from England and Northern Ireland. The Batemans, father and son of Derbyshire, were both collectors and their collections were sold on the death of Thomas’ son in the early 1890s. A large part of the collection, in particular those pieces of local provenance, was bought by the City of Sheffield and is still held at its Weston Park Museum.

In March 1895 Pitt-Rivers bought 12 objects that the Royal United Services Institution had sent to Sotheby’s for auction. It has already been noted that Pitt-Rivers’ first acquisition at Sotheby’s, in 1861, had also been objects that had been in the museum of the RUSI. At the same sale he also bid successfully for 31 Anglo-Saxon objects excavated in East Kent and from the collection of D F Kennard, possibly a hop and fruit merchant from the area. He was back at Sotheby’s in July to acquire 144 objects from the collection of Robert Greg. The bulk of the purchase was one lot consisting of 108 spindle whorls from Cyprus, France, Switzerland, Denmark, Mexico and elsewhere for which he paid four guineas (£251). Greg was a mineralogist from Buntingford, Hertfordshire, a Justice of the Peace and a keen antiquarian. It might be noted that there are two Neolithic axes from Turkey collected by Greg in the Founding Collection but no information on how Pitt-Rivers acquired them. The same month he bought seven objects from the collection of the Revd Edward Duke of Amesbury, Wiltshire. The objects cost £47.12s in total (£2,850), with a mould for casting bronze axes accounting for £30 (£1,796) of that sum.

In 1897 55 objects from the collection of the late Rev. James Beck were purchased. Stone tools from Denmark and England represented the majority of the purchases but there were also various objects from Japan, China and Russia. Little is known for certain about Beck, although some of his collection is now in the British Museum. This would appear to be the last auction at Sotheby’s from which Pitt-Rivers bought anything. There are a further 99 objects dated March 1898 and five from 1899 that derived from Sotheby’s, but they are mainly objects of unknown provenance that had escaped earlier cataloguing. It should be noted that in the last five years of life, when his health was failing, it is unlikely that Pitt-Rivers attended the sales in person. It is not known whether he was represented by an agent or whether he put in his bids on the basis of perusing the catalogues.

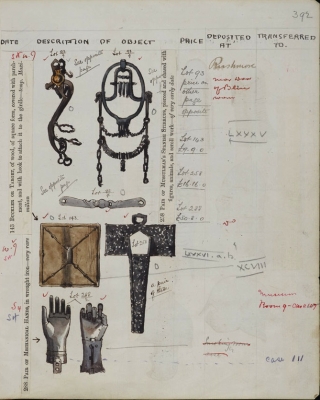

Compared with Sotheby’s Pitt-Rivers bought relatively little at the other six auction houses which provided objects for the Second Collection. Christie’s, the second most frequented, was the source of 472 objects. In 1882 he attended two of their sales; at the first he bought various locks and keys and at the second weapons and armour. Almost all the objects from both sales are of unknown provenance. In 1883 he bought a collection of Iranian pottery for £39.17s (£1,926) which had been put together by Adrian Churchill who had been consul there. In May 1884 he attended the sale of the collection of the late Albert Conyngham, later Denison (like Pitt-Rivers, he changed his name in order to inherit a large sum of money from his maternal uncle, William Denison, a banker and politician), the first Baron Londesborough, and spent £171.14s (£8,295) on 24 objects, including £56 (£2,705) on a gold torque. More of Londesborough’s collection came up for sale in 1888, and on that occasion Pitt-Rivers spent £420.16s (£25,202) on 47 objects, with the most expensive item, a pair of mechanical hands, costing £50.18s (£3,048). Londesborough (1805-60), a diplomat, was a rich and enthusiastic antiquary whose collection was of very high quality. His mother, Lady Conyngham, was George IV’s mistress. The following year Pitt-Rivers bought at Christie’s 30 objects, many of them pictures, which had been the property of a Christopher Beckett Denison, a colonial servant and politician, who does not appear to have been related to the banking family.

In 1885, Pitt-Rivers also acquired a further 77 objects at Christie’s in various sales; the items ranging from weapons and armour, to Roman coins and Asiatic pottery, including a number of objects from the collection of the second Marquis of Breadalbane. In 1886, the 17 objects purchased at Christie’s consisted mainly of silver items but there was also a portrait of a distance ancestor, Richard Sackville. The next year he bought 34 objects, predominantly portraits and Sèvres china that had belonged to the second Earl of Lonsdale. In July the same year he obtained seven pictures, three of which were sketches by John Constable and two paintings reputedly by Leonardo da Vinci.

In 1889 117 objects were bought at a number of Christie’s sales. The majority were of little known provenance other than that they originated from one of a number of European countries. There were exceptions however. These included 28 objects obtained at a sale of stone and bronze implements that came from the collection of George Roots (1807-91), a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, and an amateur archaeologist from Sussex. At this sale he also acquired what appears to be the most expensive item that Pitt-Rivers bought at auction, a complete suit of Tudor armour which cost £241 (£14,433).

After that Pitt-Rivers’ purchases at Christie’s sales fell away. In 1891 he bought just seven objects which included three that had been in the possession of Warren Hastings, the 18th century Governor-General of India. Finally, in 1893, he acquired six pictures painted by and in the collection of the artist, the late George Vicat Cole.

The next most highly patronised auction house was Stevens Auction Rooms at 38 King Street, Covent Garden. They specialised in natural history objects and ‘curiosities’, and continued in business until the 1940s. Over the years Pitt-Rivers acquired 147 objects from them, although he did not start buying from them until 1888 and bought most of the objects there in the last five years of his life. The first items he bought were an Indian parrying shield, sheath and helmet. The following year in a sale of Antiquities, Coins and Ancient Pottery he obtained 11 objects which had been collected by Canon Luigi Sciaro about whom no information is so far forthcoming. Then there was a gap of several years, until 1897, before Pitt-Rivers apparently found anything to interest him at Stevens’ sales. In that year he bought 93 objects at two sales, in May and November. The objects came from all over the world, Australia, Melanesia, Papua New Guinea, Indian subcontinent, Europe and North America, but no fewer than 35 of them were stone cores from modern Pakistan. From the November sale Pitt-Rivers bought 13 objects from the recently deceased John Calvert, a mineralogist who had worked in Australia and Peru. Finally, there may be a few objects from Stevens’ sales in 1898 and 1899, although the documentation is not clear on this point.

After that, the four other auction houses were the source of only a handful of objects. Bonham of Oxford Street, London, provided 15 objects, 11 plates and four saucers, all from a sale on 22 May 1884. The seven objects from Phillips & Co of King William Street, London were pieces of Japanese pottery bought on 7 March 1884. The three items from Debenham Storr & Johnson Dymond bought in 1897 consisted of three gold ornaments (one of which was 57 gold beads) from modern Zimbabwe. Finally there is an auctioneer local to Rushmore, Blanchard of Blandford Forum, from whom four objects were obtained in 1897, although one is listed as a donation.