To search the RPR site click here

Pitt-Rivers in Canada

Pitt Rivers in Canada (and America): The Filmer Album and Notman Studio Lane Fox Portraits, and the John Wimburn Laurie Diary Entries

Christopher Evans

![Captain [James Thorpe] Lane Fox (right), from Filmer Album page, ‘Untitled/Four Photographs’ (left; Harvard Art Museums/HUAM 317551/P.1982.359.75; in the museum’s catalogue-entry they mistakenly, if tentatively, identify him as ‘?Biddulph Lane Fox’).](../../../images/joomgallery/originals/people_and_places_3/figure%201.jpg) Captain [James Thorpe] Lane Fox (right), from Filmer Album page, ‘Untitled/Four Photographs’ (left; Harvard Art Museums/HUAM 317551/P.1982.359.75; in the museum’s catalogue-entry they mistakenly, if tentatively, identify him as ‘?Biddulph Lane Fox’).

Captain [James Thorpe] Lane Fox (right), from Filmer Album page, ‘Untitled/Four Photographs’ (left; Harvard Art Museums/HUAM 317551/P.1982.359.75; in the museum’s catalogue-entry they mistakenly, if tentatively, identify him as ‘?Biddulph Lane Fox’).

While recently researching a paper concerned with the impact of Pitt Rivers’ military career upon his archaeology, the web was widely consulted in an attempt to locate photographs of him in uniform. Unexpectedly, where a positive ‘hit’ came from was the Harvard Art Museums’ Department of Photographs. There, photographs of Captain Lane Fox appeared in two Filmer Album page-arrangements. This seemed extraordinary, as the often watercolor-enhanced photocollage albums of Lady Mary Georgina Caroline Filmer (1838–1903) now receive considerable attention in art history circles (e.g. collected by Paris’ Musée d’Orsay, as well as Harvard, etc.) and her work is seen as anticipating surrealist collages (e.g. Siegal et al. 2009).

![Filmer Album page, ‘Untitled/Fourteen Photographs’, with Captain [James Thorpe] Lane Fox shown top right (Harvard Art Museums P.1982.359.68).](../../../images/joomgallery/originals/people_and_places_3/figure%202.jpg) Filmer Album page, ‘Untitled/Fourteen Photographs’, with Captain [James Thorpe] Lane Fox shown top right (Harvard Art Museums P.1982.359.68).

Filmer Album page, ‘Untitled/Fourteen Photographs’, with Captain [James Thorpe] Lane Fox shown top right (Harvard Art Museums P.1982.359.68).

In the one setting the Captain’s full-length portrait has been stuck in alongside similarly formal-posed images of two gentlemen and two other officers: one, Captain Stewart’s is missing, with the other being of Sir Frederick Bathurst, a Lt-Colonel in the Grenadier Guards (shown in civilian garb, between 1861-65 he was MP for South Wiltshire: Fig. 1). On the other page (Fig. 2), Lane Fox’s is just a bust image, and it occurs with 13 more decoratively arranged pictures of men, women and officers, including both full-portraits and head-shots, and amongst which is Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (1841-1910).

Just how Lady Filmer obtained the Lane Fox photographs – bought as a studio job-lot or a personal gift? – is something that we’ll return to. More importantly is that the individual doesn’t actually look much like the later Augustus Henry Lane Fox/Pitt Rivers himself (e.g. just mustached and without his hallmark sideburns); in neither does he appear in uniform and in the one he looks rather dandified. Leaving this matter aside, the next point of departure is that one of the Lane Fox photographs has ‘Notman’ imprinted upon it.

Born in Scotland, William Notman (1826–91) moved to Montreal in 1856, where his photographic studio soon flourished and he is considered to have been Canada’s first photographer of international repute (e.g. see Dodds et al. 1992). Aside from individual and group portraits, he also undertook public commissions. Amongst the latter was the construction of the Victoria Bridge across the St. Lawrence River. Its opening in 1860 was attended by the Prince of Wales, to whom a series of Notman’s prints was presented; apparently so delighted was Queen Victoria by these that she named him ‘Photographer to the Queen’ and this was boldly signboarded above his studio’s front-door.

Today Notman’s photographic archive is held by Montreal’s Musée McCord Museum and its holdings include six ‘Captain Lane Fox’ portraits. Of these, four are clearly of the same individual as in the Filmer Album. Apart from the bust portrait, there are two different full-length poses and another on horseback; variously dated 1862 and 1863, in none is he in uniform (McCord Museum: 1-3510.1; 1-7031.1; 1-7060.1; 1-7990.0.1). But, then, there are also two full-length portraits, entitled ‘Capt. Augustus Henry Lane Fox’ (1862), shown in his Guards’ uniform – bearskin to one side and their winter-issue cap to the other – and, replete with sideburns and looking comfortably ‘military’, this is clearly ‘the man’ himself (Fig. 3). 1

Capt. Augustus Henry Lane Fox, Notman photograph (McCord Museum 1-2063.1; see also 1-2064.1).

Capt. Augustus Henry Lane Fox, Notman photograph (McCord Museum 1-2063.1; see also 1-2064.1).

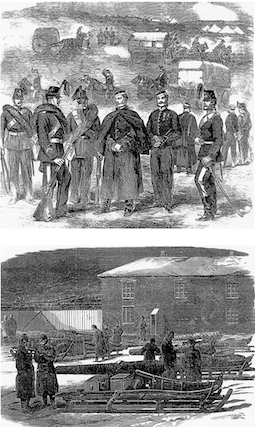

Admittedly not of earthshaking importance, for Pitt Rivers researches this is a notable finding as they are the only known images of him in uniform. Nor is the fact that he should have then posed for these portraits in a Montreal studio surprising, as it relates to his posting to Canada during the Trent Affair of 1861. Set against the background of the American Civil War and – with a rapid Union victory over the Confederate States anticipated – a fear that Canada thereafter would be invaded by the Union Army, this proved something of a diplomatic ‘storm in a teacup’ (Hamilton 1874: 321–30; Bourne 1961; Campbell 1999 and Foreman 2011: 170–95). On the 8th of November of that year, off Bermuda, the British mail steamer Trent was boarded by a Union ship and two Confederate Commissioners were removed. With the laws of the sea and British neutrality thus violated, the British War Office then made plans to reinforce the British North American garrisons; the decision being made to send troop on December 6th, with the first sailing the day after. In the end, any serious threat of conflict had subsided by the end of December (with the Commissioners released), but this was not before 11,500 troops had been dispatched to Canada and, on their arrival, some 6,800 were moved by sleigh in dead-of-winter conditions over approximately 300 miles across New Brunswick to the St Lawrence, from where they were transported by rail to Quebec City and Montreal (Fig. 4).

Prior to the Trent Affair and the decision to sent troops, the fear of imminent invasion had led to an expansion of the volunteer forces in British North America and, in September 1861, Canada asked the British Government to provide 100,000 stands of arms for them. In late October it was agreed that 25,000 would be shipped, but of these only 5,000 were sent out to Halifax prior to spring due to the icing up of the St Lawrence (Bourne 1961: 611). While these may seem rather obscure and overly detailed matters to concern ourselves with, precise dates are crucial here.

The Trent Affair: top, ‘Reinforcements for Canada – The Military Train’ and, below, ‘Armstrong Guns Packed on Sleighs in the Ordnance Yard, St. John, New Brunswick’ (Campbell 1999: figs 3 and 7).

The Trent Affair: top, ‘Reinforcements for Canada – The Military Train’ and, below, ‘Armstrong Guns Packed on Sleighs in the Ordnance Yard, St. John, New Brunswick’ (Campbell 1999: figs 3 and 7).

In the third volume The Origin and History of the First or Grenadier Guards it is recorded that Pitt Rivers shipped out on the 2nd of December, 1861 (Hamilton 1874: 321) and, as announced in the Boston Advertiser, he arrived – accompanied by ‘a servant’ – on the Cunard steamer, Canada, in January. He was officially assigned to ‘special service’ (ibid.), an intriguing phrase that could convey a hint of espionage (this being to the point that, briefly, I entertained the idea that the other Captain Lane Fox could be our man in a very accomplished disguise).[2] While as Chapman outlines this may still have entailed a more general fact-finding remit, in all likelihood it implies nothing other than Pitt Rivers’ involvement in musketry training (1981: 107). What we cannot be certain of is whether this was for British troops or the local militias. The latter would make sense given the action’s timeline, as he was sent out four days before the official decision was taken to send British troops and, therefore, he was not actually part of the main expeditionary force itself.3 Apparently the militia at the time was essentially a ‘paper force’ – “Untrained and undisciplined, they showed up in all manner of dress … carrying an assortment of flintlocks, shotguns, rifles and scythes” – and, on December 20th, companies from each of its battalions began their training (Warren 1981: 133).

Having established this as far was we reasonably may, and returning to the photographs, the next issue to broach was just who was the other Captain Lane Fox, the one that appears in the Filmer Album pictures and also had portraits taken in the Notman Studio. Obviously part of the military, there would then be two candidates, both serving in the familial regiment, the Grenadier Guards. One is Charles Pierrepont Lane Fox (1830–74), Pitt River’s cousin and who in The London Gazette of December 3rd, 1852 is recorded as participating as an official Guard-mourner in the funeral of Field Marshall Arthur, Duke of Wellington (along with the then Captain Augustus Henry). The other candidate is James Thorpe Lane Fox (1841-1906), Augustus Henry’s nephew and the younger son of George Lane Fox (II). Indeed, looking at the latter’s portraits in connection with the family’s Bingley-peerage home at Bramham in Yorkshire, this without doubt must be our other captain and who then would have been 21/22 years-old (Augustus Henry being 35 at the time of his portrait). Further confirmation of this comes from the fact that the New York Times of 04/01/1862 reported a Captain J.T.R.L. Fox travelled out on the troopship, The Adriatic, with the main Guards contingent (see also Hamilton 1874: 321).

With the other captain identified, how his photographs ended up in a Lady Filmer album can be addressed. This now seems relatively straightforward, as she apparently had a flirtatious relationship with the Prince of Wales and who was a friend of James Lane Fox. Moving in the same social circles, it is then likely that the pictures would have been a gift (and which might account for James dandyish, out-of-uniform poses).

Here, it can also be added that there is nothing special about that both of the Lane Foxs had their portraits separately taken by Notman. His archives include photographs of a number of the Trent Affair’s officers, including many of Wolseley (Low 1878).

Having resolved the matter of the Notman Studio portraits, there proved to be another twist in the tale. In the course of these searches I stumbled upon a web-site, ‘Irregular Correspondence’, that posts up the nearly 200 letters (plus selected diary accounts) of the 19th century Laurie family, whose members – like those of so many families at the time – were spread across the empire. Most pertinent is that it includes the 1862 diary entries of the son, John Wimburn (1835–1912). Born in England and Sandhurst-educated, he served in Crimea and India in the 4th King’s own Regiment of Foot (Fig. 5). [4] He also came out to Canada in 1861 on ‘special service’, eventually serving as Inspecting Field Officer of Militia in Nova Scotia and, subsequently, Adjutant-General of the same. In the spring of the next year he evidently toured ‘West Canada’ (i.e. Quebec and Ontario) and the northeastern American States, when he sometime roomed and travelled with Colonel Lane Fox (the explanatory notes below are those provided by the web-site’s editor, William Dyson-Laurie; the accompanying illustrations having been added here). Leaving on the 22nd of March, he wrote to his mother from Halifax of his trip beforehand (17/03/1862):

John Wimburn Laurie, 1859 (aged 24; from ‘Irregular Correspondence’).

John Wimburn Laurie, 1859 (aged 24; from ‘Irregular Correspondence’).

… as the weather is too bad for outdoor work, I am going on a trip to the U or Dis-U States and Canada. It is of course quite possible that the Home government may refuse to keep me out here and then I must see Niagara and the great cities not to speak of Washington, with General McClellan and his great army. I do not wish ever to re-cross the Atlantic again, so had better see all I can before I turn eastwards.

You must not be surprised therefore at getting letters from all sorts of outlandish places for the next month. At the end of which I am again to report myself here, and get my answer as to whether I am to go or stay.

I have scarcely chalked out my itinerary for the month as yet, as so much depends on the time the trains take, and the opening of the navigation, which will enable me to take short cuts, instead of going a longer way round by ocean steamers &c. I have to go a long way round at starting to Boston to get to Montreal and that thanks to snow and ice. I am going with an old friend, Fitzroy 68th, as far as Canada West, thence I shall struggle along on my own account, with my letters of introduction &c. I do not know how money will last, but I think it will be well spent in travelling in that part of the world as there is really something to see; a change on the old humdrum of Europe.

After travelling to Montreal and then Toronto (touring locally to Niagara Falls, etc.), he went by train south of the border, arriving in New York City on the 4th of April; we join him two days later:

April, 6th

Up late, Mr. Mintern Jr. and Mr. Hamilton came in. We went to Church at Trinity Chapel and afterwards walked in the Central Park, a really pretty affair and showing what taste can contrive out of the most unlikely materials. Dined with Mr. Mintern and afterwards walked in Eighth Avenue, the fashionable promenade on a Sunday afternoon. Met at the Club a Mr. Megers very civil indeed. I indulged in oysters with him and afterwards with Colonel Ross and Colonel Lane Fox strolled about and saw some good pictures, at a Mr. Mason’s and at the Century Club. Supped and chatted with Colonel L.F. and after writing, to bed.

April 7th.

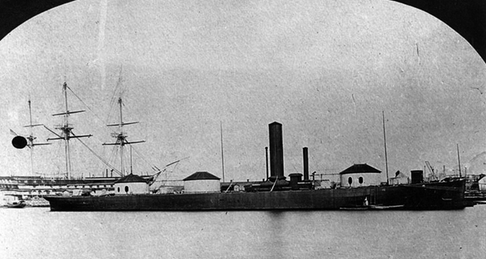

Up earlier and getting on with a letter home, interrupted by visitors. After breakfast, started to join Mr. Menzies with Colonel L.F. Looked into the Merchants Exchange, saw Mr. Whitehouse an old friend of G. and J.L. Afterwards found Mr. B. Duncan and had some oysters with him. Then on to the Navy Yard across in Brooklyn, no iron gun boats going on, but some of the transformed ferry boats seem ingenious. The “Roanoke” is being cut down and converted into an iron plated ship. Only one dry dock and that not large; the Navy Yard cannot hold a candle to Portsmouth or any other of our arsenals and dockyards, the workmen seemed loafing and idling about, not the hare busy stir that we should see at home. Came back very tired and footsore. Then strolled into Broadway to look out some notions, and hurried back late to dress for dinner at the Union Club with Colonel Munroe and Mr. Kane. Met an oddity, Mr. Jerome who entertained us with his descriptions of his own doings during the time he was collector of customs at Rochester, NY, opposite Toronto. Smart and highly seasoned, but still amusing; afterwards played a game or two at billiards and home. Yesterday received a letter from my Mother and today one from Holloway. My Mother’s dated March 1st, the other March 24th, three weeks later. Very odd that letters for me from home never turn up at the right time.

Roanoke – SS Roanoke (1857-1883) was converted from a frigate between March 1862 and June 1863, being cut down to her gun deck and rebuilt as a triple-turret armoured warship (Fig. 6)

USS Roanoke, probably as laid up in New York Navy Yard after the Civil War.

USS Roanoke, probably as laid up in New York Navy Yard after the Civil War.

April 8th.

Wrote to Mary and finished the letter to my Mother. Drove out with Mr. Douglas a.m. and afterwards walked up to see General Scott, who was however asleep. Afterwards called on Mrs. Mintern and Mrs. Whetten, saw Miss Whetten a very pleasant girl whom I tried to persuade to come to Halifax in the summer. Dined at 5½, a heavy snow storm setting in. Met Colonel Wilkinson, Grant, ... of the Fusiliers and Newquay, 16th, Hunter, F.S. Finished my letters and to Mr. Duncan’s to a very pleasant party; the girls very pretty and nice, cheerful, frank and unaffected. Enjoyed myself most thoroughly and quite sorry to part with my partner, a Miss Nevor, a great friend of Miss Pringle’s, to whom I desired to be remembered. Mrs. Jones at Tenton’s Hotel in London during the exhibition hopes I will call upon them. Full of fun and lark are the American girls and great in a ball room; they are friendly at once and quite intimate in five minutes. I don’t know when I have enjoyed a party more, unfortunately it is over; all things must come to an end. To bed about 3½ a.m. thoroughly tired out. News of the Battle of Pittsburgh, the Waterloo of America arrived.

Battle of Pittsburgh – Fought at Pittsburgh Landing, Shiloh, on the Tennessee River, (and more commonly known as the Battle of Shiloh). Confederate forces launched a surprise attack on General Grant’s Union army

Wednesday, 9th.

Up to breakfast very late as were all the rest of our party. Took Colonel Lane Fox to Colonel Munroe, and we together went to call on General Dix who commands at Baltimore and through whom the passes to Fortress Munroe must come. He was very civil but Mr. Stanton would not allow us a pass. Called on the Butler Duncans and found Col. Percy having it all his own way. Left at 5 p.m. for Washington via Philadelphia and Baltimore, passed through the former city in horse cars in a heavy snow storm; having to get out in this to lift the cars on to the “track” did not make us bless the Quakers whose desire to draw custom for their Hotels causes this break in the communication between New York and Washington. The cars were very uncomfortable, but yet we crossed the Susquehanna without knowing it in a ferry boat, the train going on in two divisions. Snow very thick all the way and laying, melting, at Washington where we arrived about 7 a.m.

General Dix – John Adams Dix (1798-1879) had been Secretary to the Treasury in 1861 and at the start of the Civil War proved himself energetic and capable. He held various appointments ending as Governor of the State of NY in 1874

Fortress Monroe – Despite its location at the south side of the entrance to Chesapeake Bay (and therefore in Virginia) Fort Monroe remained in Union hands throughout the Civil War

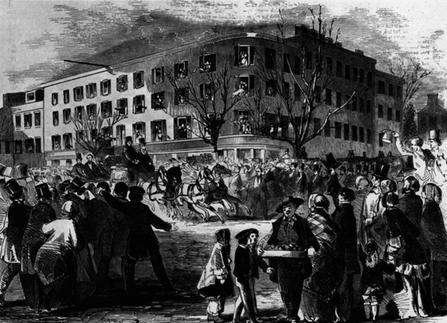

Thursday, 10th.

In the omnibus to Willards Hotel which making up beds in some 500 rooms can put more than 1000 to bed. Colonel Fox and I put up together. After breakfast found Col. Townsend full of business. Next discovered a Captain Brice Smith who was very civil and useful, and introduced me with my letter to General Wadsworth who commands at Washington. A picture of our General officers in uniform like our own, he explained what was doing and passed me on with letters directed to any General Officer with McDowell’s army in front of Washington. Afterwards dined with Lord Lyons and met Vigitolli of the All London News, also Anderson of the Foreign Office. Afterwards formed our plans and ordered horses and supplies.

Willards Hotel – On the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 14th Street, the Willard opened in 1818 and is still amongst the most luxurious of hotels in Washington (Fig. 7)

Willard’s Hotel, the arrival President Lincoln, 23 February, 1861 (from Foreman 2011: 11).

Willard’s Hotel, the arrival President Lincoln, 23 February, 1861 (from Foreman 2011: 11).

General Wadsworth – Brigadier General James Samuel Wadsworth (1807-1864) was a wealthy land-owner in New York Sate who initially served as a civilian volunteer but was quickly commissioned as a Brigadier General. He was popular with his men for his concern for their welfare. His Division suffered major losses at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863 and he died in a Confederate hospital after being shot in the head during the Battle of the Wilderness the following year

Lord Lyons – Richard Bickerton Pemell Lyons, GCB, GCMG, PC, DCL, 1st Viscount Lyons, (1817-1887) was an eminent British diplomat who had overseen the wildly successful 1860 tour of Canada and the United States by the Prince of Wales and in the Autumn of 1861 was to negotiate the release of Confederate envoys from Union custody after they had been seized from a (neutral) British mail steamer – avoiding what might have developed into war between Britain and USA

Friday, 11th.

Preparations delayed lost us much time, but we caught the Alexandria boat at 10 o’clock and got across to the depot. General McCall was away and we could not get up by train, so made a push with our horses leaving about 11½. Passed two brigades of the Pennsylvania reserve, under General McCall, on the march, very loose and straggling; covering miles of road without any formation, in almost any uniform; their knapsacks badly hung and bad that every dodge was resorted to, to carry them. Passed Fairfax Court House about two o’clock, leaving behind the outer line of Confederate entrenchments, a mere sham, thence on to Centreville arriving about 4 p.m. and feeding horse and man, 21 miles got over, roads fair, very fair for the work they have had. The Centreville position was a splendidly chosen one, the works strong closed works, connected by a trench, carefully revetted with logs, and close behind a supporting line, also closed works. A fine open sweep in front gave full play for artillery. On enquiring of an inhabitant what the rebel troops were like, I had a strong proof of the Union feeling!!! prevalent. “Rebels you call them, Southerners we call them; there were as fine men amongst them as any in your ranks”. I denied the soft imputation of being a Northerner, and we parted better friends. My first introduction to a corduroy road was on the way from Centreville to Manassas, one which Beauregard must have laid down for our especial benefit. We passed the renowned rivulet of Bull Run, to the left of the Battle field, and arrived at Manassas, which has been entirely burnt down by the Union men, just at sunset. No general was in hail, my two fore shoes were loose. I found a forge established by “contrabands” and had damages repaired. Found some officers of the Lincoln’s Cavalry quartered close by and they offered us soldiers’ fare which we frankly accepted. Our entertainers were Captain Lord, late 17th Lrs. and 2nd W.I.R., Lieutenant Prendergast and Dr. ..., all English, with a Captain ... late a Sergeant in the 90th.

Later came in a Major of a New Jersey Regiment and a Military chaplain, and still later the rest of the N.Y. Cavalry, so after a very good piece of beef we did not get comfortably settled on the floor with our blankets until very late and to sleep, hoping to wear off the stiffness.

General McCall – General George Archibald McCall (1802-1868) graduated from West Point in 1822 and retired as a Colonel and Inspector General of the Army in 1853 after 31 years service. However at the start of the Civil War he helped organise Pennsylvania volunteers and later served in the Peninsular Campaign. He was wounded and captured at Frayser’s Farm in 1862 but exchanged and released within a few months. He resigned the following year

Corduroy road – a road formed by placing sand-covered logs across the direction of the road over a swampy area. The result is an improvement over impassable mud or dirt roads, yet is a bumpy ride in the best of conditions and a hazard to horses due to loose logs that can roll and shift. This construction had been used in Roman times

Saturday, 12th.

Astir before the sun. After breakfast and looking to our horses, started onwards towards the Tappahannock. Met General Kenney’s division on the move to the rear to embark at Alexandria to reinforce General McClellan. These have more discipline than any I had before seen, and the officers looked more like business – but – a Major from one of the New Jersey regiments told me that he had above 100 of our soldiers in his ranks, and that they were generally his best men. So perhaps the superior physique that we gave the American soldiery credit for is more a myth than a fact. Certainly their men who looked to me in face and carriage most like English soldiers were about their finest men. Met several batteries of artillery returning, the men apparently loose, horses, light. Parrott and stout brass guns like the L.M.12 pr. composed their equipment. Back through Manassas, met another New Jersey Major who proposed a visit to Bull Run which we agreed to do. Picked up a Confederate deserter who told me their army was well fed, regularly paid, clothed and well armed with Enfield Rifles – so much for their inefficiency – that their discipline is poor, I believe; following Bull, came to where General McDowell should have crossed, and further on to where he did cross; the former most favourable for him, the latter almost certain defeat. Riding on, we came to the stone bridge, since blown up by Beauregard, and this obstacle gave us two or three weary miles’ ride before we could find a ford. We at last crossed by the ford near Frank Lewis’ house. Tooled along into Centreville, where we fed. The road is a turnpike road was good enough, altho’ stony and rutty, but B. and Jeff Davis having destroyed the bridges, left us no alternative but to wet our saddle flaps and legs in crossing the River. Pushing on past Fairfax, we met the Lincoln Cavalry and after an affectionate adieu bid to their Colonel McReynolds, on we went with the English A.S., passing towards the long bridge. This however was broken, had been so a week, and hence we had to make a further five mile detour to get over the aqueduct bridge and round by George Town into Washington, and this not without being insulted by the men on guard. Tired out, horse and man, we got to the stables about half past eight o’clock, and after a wash, we appreciated what American Hotels are. On asking for some hot supper, we were told we were five minutes too late and could not have any. So supped outside and, after a luxurious warm bath, turned in, rising again stiffer than ever.

Parrott and stout brass guns like the LM 12 pdr –2.9-inch (10-pounder) Parrott Rifle. This iron cannon was rifled and fired an elongated shell made specifically for the gun. Designed before the war by Capt. Robert Parker Parrott, this gun was longer than a Napoleon, sleeker in design, and distinguishable by a thick band of iron wrapped around the breech. Parrott Rifles were manufactured by the West Point Arsenal in Cold Spring, NY and also made in 20 and 32-pounder sizes. The 10-pounder Parrotts used during the Gettysburg Campaign had an effective range of over 2,000 yards. Confederate copies of the Parrott Rifle were produced by the Noble Brothers Foundry and the Macon Arsenal in Georgia. Parrott Rifles in 10 and 20-pounder sizes were sprinkled throughout some southern batteries

Model 1857 12-pounder bronze. Commonly referred to as the "Napoleon", this bronze smoothbore cannon fired canister shot 300 yards or a twelve-pound ball or an explosive shell up to a mile and was considered a light gun though each weighed an average of 1,200 pounds. The Napoleon was highly regarded because of its firepower and reliability. Most Union Napoleons were manufactured in Massachusetts by the Ames Company and the Revere Copper Company. Confederate industry replicated the Napoleon design at several foundries in southern states. The Confederate design differed slightly from Union-made guns but fired the same twelve pound shot, shell and canister rounds

General McDowell – Irvin McDowell (1818-1885), commanded the Union army in North East Virginia at the First Battle of Bull Run (July 1861). This was the first serious land battle of the Civil War and its outcome was a Confederate victory, resulting in his immediate replacement by General McClellan

Beauregard - Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard (1818-1893) was a Louisana-born American military officer, politician, inventor, writer, civil servant, and the first prominent general of the Confederate States Army during the Civil War

Frank Lewis’ House – The farmhouse used as the Confederate General’s (Joseph E. Johnston) headquarters during the First Battle of Bull Run

Jeff Davis – Jefferson Finis Davis (1808-1889) was an American statesman and leader of the Confederacy during the Civil War

Lincoln Cavalry - 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, organised in New York by Col. Carl Schurz, succeeded by Col. Andrew T McReynolds, under special authority from President Lincoln

Sunday, 13th.

Wondered and loafed about, meeting William Couper, Charteris, etc. After leaving our cards upon Lord Lyons, dined and said goodbye to our friend Brice Smith and just saved the 5 o’clock train for New York. Passed the most miserable night in the cars with the wretched Quaker break at Philadelphia where, as usual, the horse rail car ran off the track. We arrived however in New York and got across the ferry from Jersey City.

Monday, 14th.

About 5½ a.m. Slept out, and up about 10½. Drew a cheque for £10 on Cox & Co. Thanks to Mr. R. Dimwiddie. Dined at the Hotel and after dinner when to Wallack’s Theatre and saw a most stupid piece put on the stage, Love and Money, for writing which D. Boucicault ought to be kicked. Afterwards showed Lane Fox the Canterbury and some other music rooms; disappointed, fried oysters and home.

Wallack’s Theatre – Lester Wallack (1819-1888) was an American born performer who created Wallack’s Company which appeared in a succession of his theatres, at this time situated at 844, Broadway

This is the diary of a young man, with Laurie then being 27. While interested in technological developments (e.g. the state of train service and the modification of the SS Roanoke), the character of local girls almost seems to have made as much an impression upon him as military matters. Colonel Lane Fox is only named six times, though presumably that, after meeting up in New York, they were together throughout this time. They evidently travelled together to Boston, leaving there on the 16th of the month, as the day after the Boston Advertiser listed them both as passengers on the steamer, Niagara; Laurie only back to Halifax, with Pitt Rivers destined for Liverpool.

Aside from recording visits to battlefields and Civil War troop-encounters, the diary entries have them visiting a picture gallery and music rooms together; there is, though, no mention of them attending any museums, despite for example the Smithsonian Institution’s collections having been opened five years before. Noteworthy is that while in Washington they dined with Lord Lyons (Lane Fox’s attendance admittedly having to be presumed), he then being Britain’s envoy in Washington and, having resolved both the Trent Affair and, earlier, the San Juan Island crisis, was widely considered to be one of the nation’s most successful diplomats.

The question finally needs to be raised just what Lane Fox was then doing in America: was it simply a case of opportunistic homeward-journey travels or did he tour more widely before arriving in New York? Apparently visiting of the American Civil War troop deployments was a common past-time amongst the British officers in Canada once the spectre of the border conflict had subsided (Campbell 1999: 62). The fact that he toured at all raises the possibility of whether he collected material whilst there, as Laurie evidently did in Montreal: “Packing up and preparing for flitting. Much bothered as to the disposal of some Indian work which I felt bound to purchase as part of the wonders of the country and having purchased have to carry” (28/03/1862). Equally, did Pitt River have the chance to encounter local native communities? With these future research themes highlighted, it is for this reason that this simple tale of source-detection must be considered a work in progress, and that further, more in-depth studies will surely arise from his Canadian sojourn.

Christopher Evans

Notes

[1] As indicated in The London Gazette of December 13th, 1861 (pg. 5374), he was ‘to be employed upon a particular service’ (see below) and, unusually, is listed as simultaneously holding the rank of lieutenant-colonel and captain. Having obtained that ranking in May 1857, it is difficult to understand just what this implies. Indeed, on returning to England after serving in Malta, and having received criticism for his training methods there, his exact military status then seems somewhat ambiguous (he only being publically cleared of these accusations early in 1861). Living in London, it is said that he then undertook ‘regimental duties’ (Thompson 1977: 26–7; Bowden 1991: 18–20), but in the list of Guards’ officers at the time of the Trent Affair he does not appear as the First Battalion’s Musketry Instructor, that falling instead to one Captain Fitzroy Clayton (Hamilton 1874: 321).

[2] This being precisely what Lt-Colonel Garnet Wolseley did. Having also arrived in the immediate aftermath of the Trent Affair and briefly serving as Deputy Quarter-Master, he took a two month-long leave of absence and, secretly travelling south to visit the Confederate positions, met both Generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Sympathetic to the cause of southern independence (believing that slavery would then quickly die out), he published his travels, ‘A Month’s Visit to the Confederate Headquarters’ in the Blackwood’s Magazine (Low 1878: 239–72; see also Foreman 2011: 303–14 and note 45 concerning Captain Edward Hewett’s 1862 tour around the North, from which he prepared a report for the army).

The Boston Advertiser notice lists 29 other officers en board the Canada, including Wolseley [sic ‘Wosley’] who had left England on December 7th in Melbourne, but after a slow passage, embarked from Halifax to Boston (the St Lawrence then being iced-up) and from there proceeded overland. Apparently while they were wary of an uncivil reception in Boston, given the tense political situation, the citizens treated them ‘most respectfully’ (Low 1878: 244–6).

[3] On the whole, however, nothing particularly extraordinary need be implied by the term ‘special service’. A number of the officers who sailed out on December 7th of that year also went out in that capacity (including Wolseley and Quartermaster-General, Colonel McKenzie), their role simply being to prepare for the reception of troops (Low 1878: 243).

[4] Aside from being a Grand Master of Nova Scotia’s freemasons and president of the province’s Central Board of Agriculture, Laurie also served in the North-West Rebellion campaign of 1885 and eventually achieved the rank of Lt-General; he was also an MP in both the Canadian and British Houses of Parliament (Denslow 1959: 62; Totton 2007: 129–31).

Bibliography

Bourne, K. 1961. British Preparations for War with the North, 1861–1862. The English Historical Review 76: 600–32.

Bowden, M. 1991. Pitt Rivers: The Life and Archaeological Work of Lieutenant-General Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, DCL, FRS, FSA. Cambridge: University Press.

Campbell, W.E. Major 1999. The Trent Affair of 1861. The Army Doctrine and Training Bulletin 2: 56–65.

Chapman, W.R. 1981. Ethnology in the Museum: A.H.L.F. Pitt Rivers (1827–1900) and the Institutional Foundations of British Anthropology. D.Phil. Dissertation, University Oxford.

Denslow, W.R. 1959. 10,000 Famous Freemasons (Vol. III) Trenton, Mo.: Missouri Lodge for Research.

Dodds, G., Hall, R. and Triggs, S.G. 1992. The World of William Notman. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Foreman, A. 2011. A World on Fire: An Epic History of Two Nations Divided. London: Penguin Books.

Hamilton, F.W. Lt-General 1874. The Origin and History of the First or Grenadier Guards. London: John Murray.

Low, C.R. 1878. A Memoir of Lieutenant-General Sir Garnet J. Wolseley. London: Richard Bentley & Son.

Siegal, E., Bello, P. Di and Weiss, M. 2009. Playing with Pictures: The Art of Victorian Photocollage. New Haven CT.: Yale University Press.

Thompson, M.W. 1977. General Pitt-Rivers: Evolution and archaeology in the Nineteenth Century. Bradford-on-Avon: Moonraker Press.

Totton, G.E. 2007. Prairie Warships: River Navigation in the Northwest Rebellion. Surrey, BC: Heritage House Publishing.

Warren, G.H. 1981. Fountain of Discontent: The Trent Affair and the Freedom of the Seas. Boston: Northeastern University Press.